Non/Belonging in the Classroom

Non/Belonging in the Classroom

Overview

The issue of belonging and non-belonging in the university is not new. The academy’s history as an exclusive place for society’s elite has excluded many people from higher education and education in general. This means that students from historically and presently excluded groups often face feelings of doubt, unbelonging, and invalidity in these institutions. Barnard College, an institution with the mission of including and empowering young people, has many initiatives that center their voices and perspectives, however, that does not mean that the feeling of non-belonging has disappeared. There are numerous identities and experiences, both visible and not, that go largely unacknowledged or ignored in our learning environment causing students to feel that they do not belong here. Such feelings alter performance, wellness, graduation rates, quality of life, career outcomes and more. Though this is not a situation unique to Barnard, it is necessary to consider how instructors approach teaching in ways that can either exacerbate or mitigate the effects of non-belonging in an institution that has historically served predominantly wealthy, white, cisgender women. This section considers what it means to belong, how to center belonging in the classroom, and how students can recognize and exercise their right to learn, take up space, ask for help, and exist comfortably in this learning community.

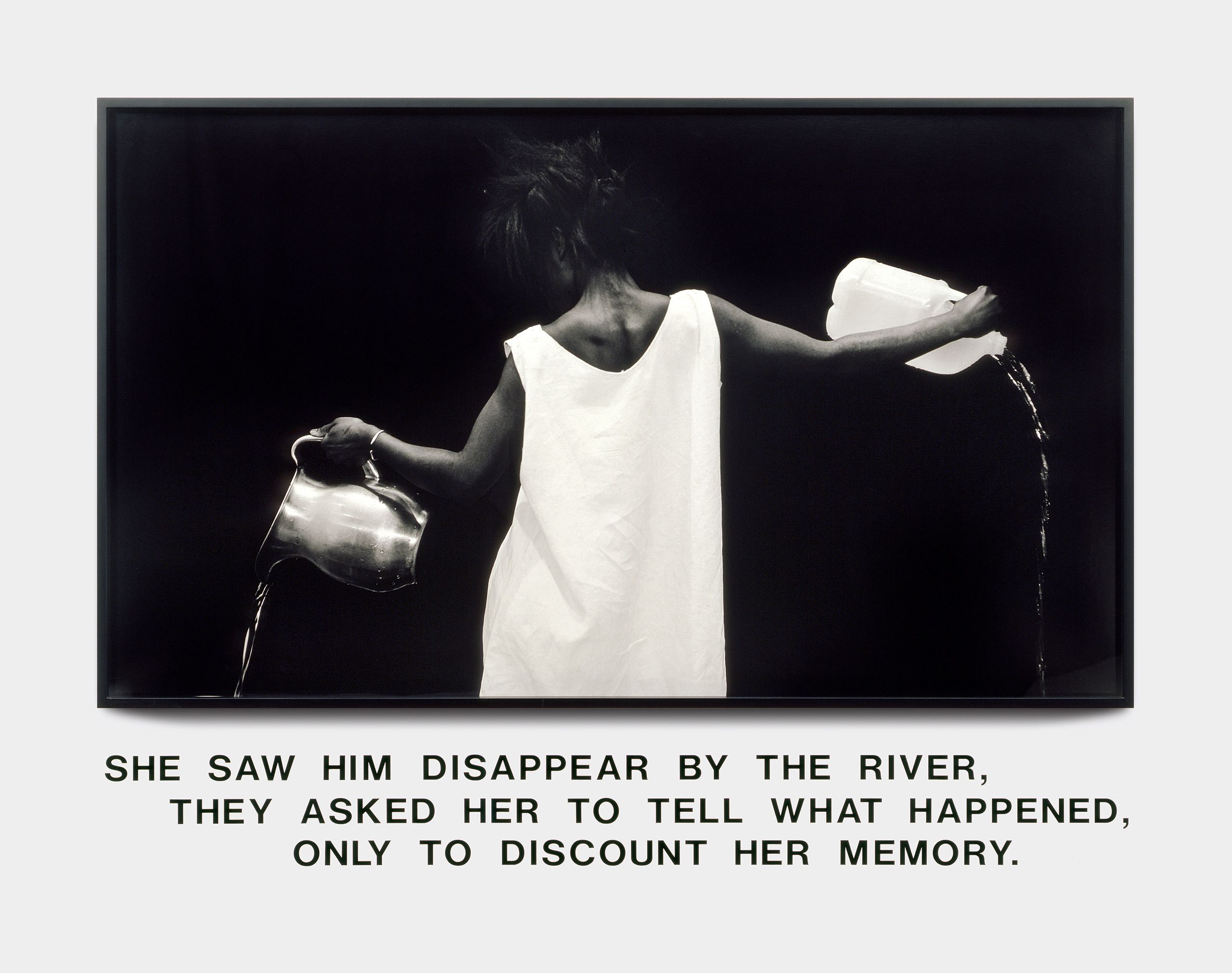

The cover image for this subsection is Waterbearer (1986) by Lorna Simpson. Simpson is a black feminist artist who is well known for her critical explorations of Black women's visual figuration within the push and pull of desire and abjection, solicitation and disavowal. Waterbearer, which, like many of Simpson's photographs during this time, presents viewers with only the back of a Black woman dressed in a nondescript white shift dress, raises questions about testimony, the politics of memory, and the imposition of forgetting, particularly as the weight of these subjects are unevenly borne in an anti-black and patriarchal world. Simpson's exploration of how the tension between demanded and discounted speech shapes the possibilities of Black women's public appearance resonates with this subsection's critical consideration of the feelings of alienation that emerge within ostensibly inclusive educational contexts.

Practices

Barnard students have a vast array of experiences, come from a broad range of places, and hold many viewpoints, all of which suggests that although we all ended up at Barnard, we got here in different ways. If instructors make certain assumptions about students in a classroom—for example, assuming that they all came to a major in a certain way, read a certain book, had access to specific information or had experiences particular to a select group of people—they exclude those whose backgrounds and lived realities do not fit into any sort of “archetypal” experience. Assumptions like these can make people feel that their experiences or upbringings did not prepare them for college, and in some cases, can make them feel that they do not have a place in the academy at all. This hinders a student’s ability to participate actively in a class and feel that their presence is welcome. On the other hand, it is important to recognize that though people are part of larger systems of race, class, nationality, and more, their experiences will always be personal and unique to them. Given that students are not automatically the experts on their own culture or country, it is important to avoid pressuring them to represent experiences they may not have or may not feel comfortable sharing. Students may feel more comfortable, empowered, or engaged as learners when they are made to feel that their participation matters even when they are not standing in as representatives of large groups of people. To put it simply, to feel exoticized is to be made to feel that one does not belong. In order to counter this phenomenon, it is always helpful to ask questions rather than assume answers, and when asking questions, to keep in mind one of the principles of affirmative inquiry: “[one’s] need and/or desire to know, learn, or experience must be subjugated to the agency of others to answer [their] inquiry” (Petryk and Fisher 10). In practice, this means that students should be invited but not assumed to relate to material that connects to their visible identities or experiences, and that no one should be compelled to represent or speak on behalf of large groups of people for the benefit of others.

According to its mission statement, “Barnard College aims to provide the highest-quality liberal arts education to promising and high-achieving young women,” a laudable goal that should also include exposing all members of this community to scholarship and material from around the world. Academically, this means making a truly transnational, interracial and multicultural curriculum that is inclusive of all identities, in which texts appear not as diversity or token projects but as materials that students can learn from and engage with fully. How might the learning experience change, regardless of its subject matter, if one deliberately sought out material that comes from outside a Euro-American lens—that was published and peer reviewed outside the United States or that was written or published in languages other than English? Such changes can open up myriad learning opportunities, affirming that all knowledge is equal and valuable, and can create space for non-American students to recognize histories of knowledge that would enable them to develop a feeling of belonging on campus. Alongside these changes in representation, highlighting the work of scholars who read canonical texts through post-colonial, anti-racist, feminist, and queer lenses can encourage students to develop alternative forms of knowledge production. This process discourages the deficit-model thinking that Marisela Martinez-Cola and her former students argue is common when classes focus on social oppression and power. Broader representations of humanity, as well as broader approaches to the study of humanity, can allow students who are excluded in different, although often intersecting, ways (i.e., international, BIPOC, low-income, and LGBTQIA+) to believe they are valued in the academy.

All students engage with and process course materials differently, and certain course material may be triggering for students, especially in times of political and social unrest. Therefore, faculty should ensure that there is appropriate time and space in class to address reactions to course material and how it interacts with lived realities. This means understanding that everyone has their own way of reacting and may need space set aside for feeling, grieving, and processing within the classroom as well as outside of it. This may come immediately or it may need to be accommodated for later on in the semester, but it is necessary to ensure that students feel that their way of grappling with material belongs in the classroom and can be held by and within a classroom setting. Make space for students to speak earnestly when they wish to do so, but do not expect them to share or even have a fixed opinion on discussed materials. One can make space by creating flexibility in the syllabus and assignment content, especially when people have different needs and capacities when engaging with an assignment and its requirements. This can include but is not limited to leaving room for student input on readings and assignments; being flexible with due dates and the scheduling of material if students need more time to discuss or process certain topics; and leaving room within and after class time or developing feedback mechanism (like exit tickets) for students to be candid about their reactions and feelings regarding the nature of the course content. (“I am staying after class if you would like to talk about anything in private.” “If you need space during class, please take the time to turn your video off/leave the room.”).

As noted before, Barnard students, faculty, and staff come from a wide array of backgrounds where no two people have the same lived experiences. This means that there is always something to be learned, and faculty have as much to learn from students as students do from faculty. As instructors change their syllabi in order to be more inclusive, they must become comfortable making mistakes, being corrected, and learning with their students. This requires everyone in the class, and especially instructors, to embody a posture of humility in response to feedback, which means refusing to dwell excessively on mistakes and implicitly burdening students with the task of forgiveness during class time. See the subsection on Instructor Position and Power for further comments on this and the importance of not leaving it to students of color to address racism in class materials or interactions.

Ensure that students are aware that they can speak to other members of the community, not just instructors, if they need help. Instructors should also recognize that they do not have to be the only resource for students, and can feel free to utilize the CEP’s feedback map when directing students to support on campus.

Reflective Questions

For faculty

How do I define belonging in my classroom? What proactive measures can I take to ensure my students recognize that they belong in my classroom? How can I practice recognizing when my students may need the space and time to grieve and address their emotions?

For students

Who do I feel comfortable talking to about feeling a sense of belonging and non-belonging in the classroom? What can I do, in tandem with faculty, to help my peers feel like they belong? What might I need to approach an instructor to ask for the space I need to address my emotions and process potentially harmful course material?