Equity and Accessibility Online

Equity and Accessibility Online

Accommodations and Accessibility

Provided by Holly Tedder, Director of the Center for Accessibility Resources & Disability Services, Barnard College

Consider students’ accommodations when planning take-home exams

Consider whether students who are ill or have a disability may need additional time to complete take home exams. Have a plan for extension requests. If you’ve set a time limit on Canvas for turning in an assignment, be sure to communicate with students who have extension accommodations regarding how they can turn in the assignment with their extended deadline.

Use universal design principles online

Make slides/notes/recordings available through Canvas after live streaming. Class lectures can be recorded in Canvas using Big Blue Button, or through Zoom. Consider whether you will require remote teleconference attendance for these lectures, or whether there are other ways for students to demonstrate engagement with the material (discussion posts, response papers, etc.). Find out more about universal design for learning at the CARDS website.

Adjust online exams for students’ accommodation

You can adjust specific students’ accommodations so that they are able to receive their extended time. We recommend that you cross-reference the information in the AIM Faculty Portal as you’re setting this up.

View students' accommodation plans within CARDS’s AIM

You are also able to download an Excel file with students’ specific accommodation eligibility available in a spreadsheet.

Contact CARDS

If you have questions about students’ specific accommodations plans and how to implement them notify the CARDS office.

Additional Information

Zoom Considerations for Teaching Students with Disabilities

The following tips may be useful to consider when teaching with Zoom. Not only can they improve the learning experience of students with disabilities, but some of these approaches may also help those students participating by phone, those with wifi challenges, or whose first language is not English. Please note: The whiteboard and polling features in Zoom are currently not accessible for people with motor or visual disabilities. If you use these tools, you may need to work with your students on suitable accommodations.

Real-time captions

If your student has a need for real-time captions, their CARDS Accommodation Plan should indicate this. Please contact CARDS as soon as possible to arrange for remote CART or other live captioning options.

Keyboard shortcuts

Send out the Zoom Keyboard Shortcuts ahead of time for anyone with a temporary or permanent disability that may make it challenging to use a full keyboard when participating.

Audio descriptions of visual materials

Describing content that is displayed on Zoom will help anyone with vision or learning disabilities, as well as students who need to call in due to internet issues.

Managing participants’ questions

There are several ways that participants can ask questions in Zoom: by raising their hand, unmuting when called upon, or by entering the question into the chat. Please keep in mind that some students may not find it easy or even possible to access the chat window and the main Zoom room simultaneously, and those using a screen reader to listen to the chat may encounter audio interference with the conversation in the main room. Whenever possible, sticking to a single communication mode within Zoom will make learning easier for a wide range of students.

Repeat questions

If you are hosting a Zoom meeting and choose to have students write questions in the chat, try to repeat the question for everyone to hear before answering it. Consider asking another student to help manage side conversations in the chat, and to share the questions and comments at regular intervals with everyone in the main Zoom room. This practice will be helpful to students with a variety of disabilities that make it difficult or impossible to attend to multiple streams of information at the same time.

Links in Zoom Chat

If students in your class require assistive technology, we recommend that you do not post important hyperlinks in the Zoom chat. The assistive technology some students use will not be able to activate any links embedded in the chat. You can instead share links and resources before or after the meeting through email or on Canvas. If other participants post links in the chat, remember to share (or designate a student or teaching assistant to share) those links with the class by email or through Canvas. You can also save the chat before ending the meeting to distribute as a text file to your students after the session ends.

Don't require that students have their camera on at all times

Students who experience panic attacks may need to step away from the class for a few minutes. Others with chronic medical conditions may need a quick break or to step away to the bathroom. Others with social anxiety may not feel comfortable leaving their camera on in general, or having others see their home environments. Others may simply not have a reliable internet connection. We recommend being clear about your expectations for camera use if it's strictly necessary for your class, but in general we don't recommend requiring that all students have their camera on at all times.

Spotlight the speaker

If you’re using Zoom in a seminar or smaller section, you might consider using the “Spotlight” video feature to make the current speaker larger and more visible to the class. This can assist with lip-reading and other techniques students use to communicate.

Record your lecture and post it to Canvas

This ensures that students in other time zones, with spotty wifi, or those in need of recordings for disability-related reasons have access to course content.

Inclusive Pedagogy Online

Inclusion and Access in Remote Classrooms

In our contemporary context of a necessary and sudden shift to online teaching and learning, we have decided to focus our recommendations on inclusive teaching on questions of access and the various challenges that distance learning imposes on producing an inclusive and accessible course. Inclusion may be defined as ‘a process of increasing participation and decreasing exclusion from the culture, community and curricula of mainstream schools’ (Booth et al., 2000) but this process can take many diverse forms in the classroom and as a result inclusive practice can vary widely. Access is a vital part of inclusive practice, a key to ensuring that such a rich learning community for everyone can be cultivated and created. Access may be defined in different ways: it can be characterized by the effects of a ‘digital divide’ on students, teaching assistants and professors—the gap in access to technology (devices, internet speed, software) by socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, age, geography and/or gender. Access can also, however, importantly include content and language, literacy and education, and community and institutional structures. All of these aspects of access relate to the prior exposure and experience to technology and digital literacy in the prior formal and informal educational settings of all members of the classroom community: students, teaching assistants and professors.

Suggestions for Inclusive Pedagogy Online

Our suggestions focus on inclusive pedagogy as it specifically pertains to online teaching and learning, understanding that inclusive pedagogy encompasses a much wider range and offer ideas about how to anticipate and approach the diverse ways in which inclusive pedagogy may be practiced in online teaching and learning environments. They start from the premise that inclusive pedagogy, whether online, HyFlex or in person, is characterized by ‘the development of a rich learning community characterized by learning opportunities that are sufficiently made available for everyone, so that all learners are able to participate in classroom life’ (Florian & Linklater, 2009). Creating an environment in which all learners experience equal participation depends upon a number of factors, including but not limited to: sensitive attention to race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and socioeconomic background, open dialogue and debate about important and difficult issues and a sustained working together amongst students, professors and teaching assistants to create a sense of intellectual and emotional belonging in the classroom.

Consider recommending students change their time zones in Canvas to avoid any confusion with synchronous class meetings and due dates. Also Include your course meeting time and important due dates and times in multiple time zones on your syllabus. Be mindful of websites and platforms that may be inaccessible for your students depending on their geographical location (YouTube, for example, does not work in China, Iran, Syria or Turkmenistan and some content is limited depending on geographical region). Downloading content that is restricted in some geographical areas and posting content that way can avoid problems that may arise using links only.

Inclusive content online is very similar to building an inclusive classroom that is face to face, but there are some differences. The online environment could provide a generative context for considering online representations in the context of a range of diversity and difference and for examining how media literacy (and the lack thereof) relate to the interpretations of those representations. The online environment also has the potential to be conducive to a more collaborative atmosphere of sharing resources, ideas and materials than in a traditional face-to-face classroom.

Creating a classroom community agreement about online connectivity could help everyone to understand what students will do if s/he/they encounter connectivity problems during a class session and what the professor’s backup plans are should s/he/they encounter problems during online teaching. Access Barnard and ATLIS are vital supports for students, faculty and staff with connectivity and hardware access issues.

Including a section on Zoom etiquette can help to clarify expectations about synchronous class meetings. How the “raise hand” function should be used (if at all), how and when to “mute” and how to signal agreement (are you encouraging students to use the “thumbs up” or “applaud” functions?) and what types of Zoom backgrounds students, faculty and teaching assistants use will be helpful for building the online classroom community. Also consider your policies about camera usage in synchronous sessions. Are you requiring all students to have their cameras turned on during all sessions? Are there allowances made for students who either do not feel comfortable turning their cameras on or do not have the bandwidth to keep their cameras on? Is your classroom community comfortable with having everyone use a uniform Zoom background used? Consider that all students, faculty and teaching assistants may not feel comfortable with being on camera and/or showing their immediate surroundings on camera.

Getting a clear sense of your students’ access to reliable internet, a tablet, laptop or desktop and a quiet place to join your class online could be very helpful for assessing what adjustments might be necessary for individual students. This could take the form of a Teaching Online Planning Questionnaire that students fill out before the course begins and that is followed up with individual conversations with the professor and/or teaching assistant. The questionnaire can address the students’ needs, preferences and prior experiences with online learning. This or any other questionnaire and conversation should acknowledge and be sensitive to students’ privacy as you discuss their individual circumstances. These privacy issues can relate to students’ socioeconomic status but also to their pronoun preferences; some may prefer, for example, to share their pronouns with the class members but others may not feel comfortable doing so.

The issues of privacy and surveillance go far beyond zoom-bombing to the serious encryption issues that have been detailed in a recent University of Toronto report that details the platform’s encryption weaknesses. While it is uncertain at this time whether the College will move to another platform, it may be helpful to bring these issues up early on in and throughout the semester what your classroom community will be able to do to mitigate them so that everyone feels comfortable.

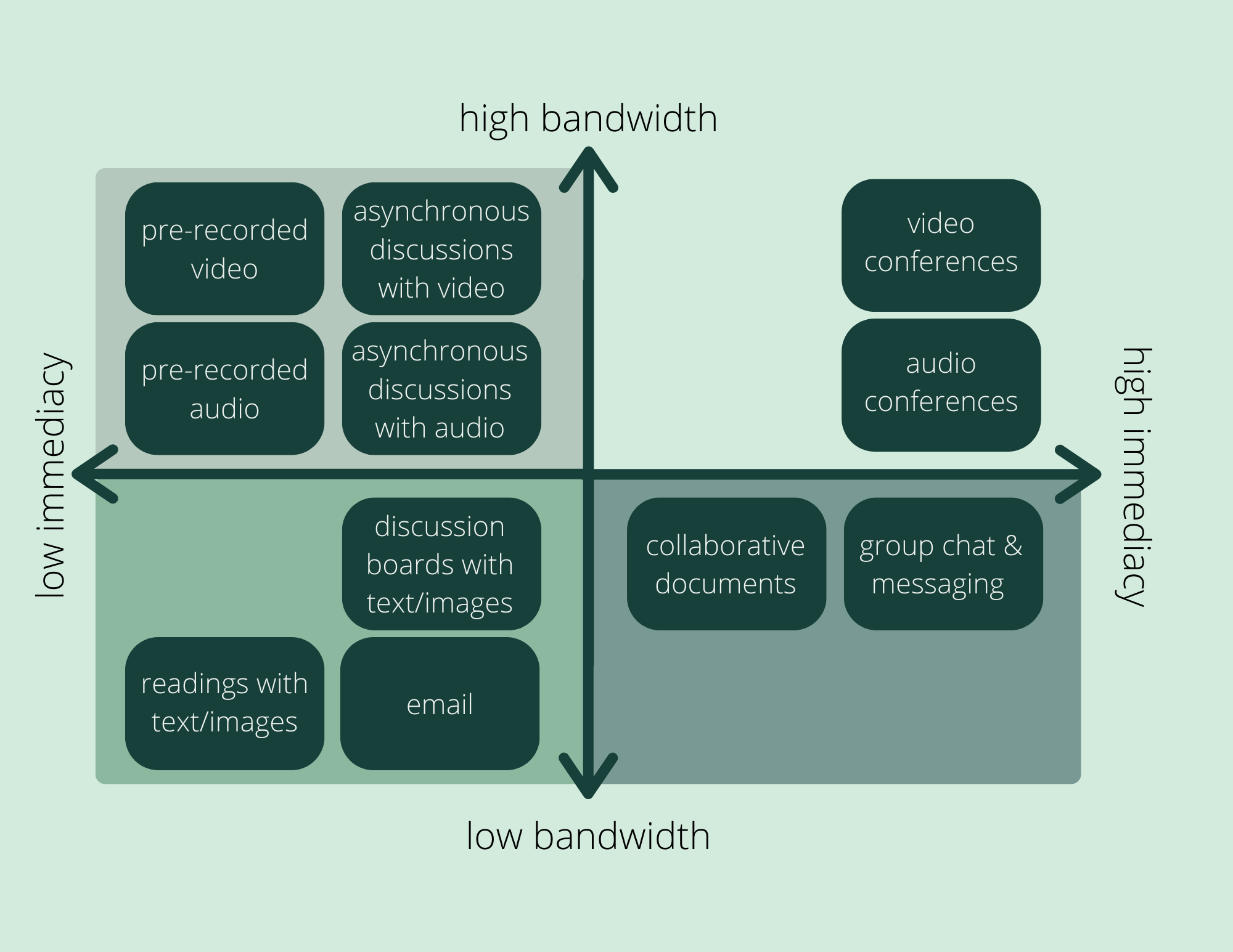

Include materials that cover a range of bandwidth, taking care that the materials are evenly distributed between high and low bandwidth or choose to weight your course with medium and low bandwidth content such as slides and article pdfs. The diagram below, created by Daniel Stanford, shows the range of mediums that one may include to balance between high bandwidth activities (synchronous Zoom classes) and low bandwidth (pdfs and texts shared on a Canvas discussion board). Stanford also distinguishes between “high immediacy” (expectations of a quick or instantaneous response) and “low immediacy” activities (expectation of a response in a specified time, but not immediately). Considering your course from the perspective of both bandwidth and immediacy may be helpful in determining which activities truly require, for example, a synchronous Zoom session (high bandwidth, high immediacy) and which would be better realized via a prerecorded video (high bandwidth, low immediacy).

Incorporating lower bandwidth materials and activities could help students who have internet access issues and thinking about your course in terms of bandwidth and immediacy may be useful in determining which activities truly require a synchronous online meeting, rather than viewing a synchronous Zoom sessions as the default means of having the classroom community come together.

For both synchronous and asynchronous meetings, providing transcripts of audio and video will ensure accessibility, as will making sure that slide material is sufficiently narrated so that students with visual disabilities or who cannot view the slides easily for any other reason. Be sure that content is mobile friendly for students who may need to access materials on their mobile phones and for students who need to use screen readers. Consult the Center for Accessibility & Disability Services (CARDS) for support making your course content fully available to all members of your classroom community.

Share your own capacities, fears and experiences with navigating the “basics” needed to run a course online - and not limited to technology. Such sharing can also help with the sense of community and solidarity within that community of everyone involved in it - professors, students, teaching assistants and all of the individuals and centers that support them.

Checking in with the class as a whole on a regular basis about how the course is going from the standpoint of their accessibility to the synchronous sessions and asynchronous materials and components can be important for making any necessary adjustments that need to be made. Regular check-ins also reassure the students that their holistic accessibility to the course is a priority. Checking in about other types of accessibility in the course, i.e. as related to course content is as vital as checking in about access related to tech and wifi issues.

The context in which we are all living, teaching and learning is fraught with peril, uncertainty and potential: we are in the midst of a global pandemic, increasing economic precarity and socio-political upheaval. Global, local, institutional and personal circumstances are changing rapidly. Regularly acknowledging, respecting and being receptive to the different and shifting ways in which this context manifests itself for every member of the classroom community (including the professor) is an act of care itself.

Low-Tech Hacks for Online Teaching

Online teaching and learning is replete with challenges and potential for both students and instructors, including how to navigate low-bandwidth environments and how to use technology deliberately, selectively and effectively for pedagogical creativity. How to find low-cost solutions to navigating all aspects of the online environment can be by turns frustrating and inspiring (USC Professor Emily Nix’s DIY lightboard for her economics courses is one example of an inventive hack) as can be how to incorporate technology into your classroom so that it enhances but does not overwhelm.

We offer some suggestions below for navigating low-bandwidth environments and ideas for low-tech approaches to the online classroom.

Keep your own computer running as fast as possible

A few fairly simple steps will help to keep connectivity and will avoid frustration when uploading and downloading materials and while conducting live Zoom class sessions. Delete large programs and files and make sure virus protection software is running properly. Check for updates and allow them to run and consider installing a program that regularly scans your system and removes unwanted and unused files. Close all unneeded windows during video conferencing

Find the potential in low-tech and low-bandwidth programs

Using Google docs for peer workshopping and communal editing can both be incorporated into learning goals and help to cultivate classroom community. A Google doc could also function much like hypothes.is when used to annotate a text that is available outside of PDF format. Canvas discussion groups that start conversations, engage debate and share resources can become the catalyst for invigorating live discussions.

Consider what technology is really essential for your course and approach

Consider your course and its assignments from a holistic pedagogical perspective to determine if and when high-tech and high-bandwidth programs and activities are truly contributing to learning outcomes. The diagram linked in this article about low and high-bandwidth teaching may help in making that determination.

Provide Multiple Low-Bandwidth Access Points

Audio transcripts from Zoom (note: these are not perfectly transcribed and may need editing), lecture outlines, summaries and PDFs of powerpoint presentations and even scans of handwritten lecture notes are all ways that students can access class materials outside of live Zoom sessions. Powerpoint allows voice recording so that audio can accompany slides without needing to seek out another program like VoiceThread.

Take advantage of Open Educational Resources (OERs)

Using Open Educational Resources can be helpful to supplement your course. Resources such as MITOpenCourseware, the Community of Online Research Assignments and many of the others listed here could be valuable additions of textual and visual materials that are already readily available and need not be created from scratch or sourced and then downloaded or scanned. Here is a helpful beginning list of OERs put together by Emory University.

Use a diverse array of mediums and online communication platforms to accommodate all students

Offering office hours over the phone can be helpful for students with lower bandwidth. WhatsApp is helpful for international students as it offers free international calls and texts and is more comprehensively available internationally than Skype. Consider giving feedback via audio, too, as it loads much faster than video and can be accessed more easily for students who do not have access to high speed internet on their phones or computers.

Come online regularly and at key moments

Posting class announcements, links to online events related to your course and course updates is important for maintaining clear communication with students. One on one meetings and online exchanges with students can also become more deliberate and effective with regular communication to the class as a whole.

Remember the value of asynchronous communication and regular check-ins

Feedback is especially essential for students during distance learning, particularly in our current precarious and ambiguous circumstances. Timely replies to emails, regular updates about course materials and generally being attentive to students’ needs for communication and clarification goes very far to reassure students and help to cultivate classroom community. A simple “popcorn” style check-in at the beginning of each class session, asking students for regular feedback on the course throughout the semester (via exit tickets or another method) and sensitively acknowledging the extraordinary circumstances during which we are all teaching, learning and living may ultimately be just as (or even much more) valuable than incorporating multiple complex educational technologies into course design.