Instructor Position and Power

Instructor Position and Power

Overview

Instructors, like students, are people who each hold a unique social identity, come from many different walks of life, and have varying levels of job stability. In addition to their own personal identity and standpoint, instructors hold a relatively high position of power in the academic life of students, both in and beyond the classroom. Every instructor’s identity will undoubtedly impact the way they interact with students and their course material, as well as how students interact with them and their course material. As such, it is imperative for every instructor to reflect on their position of power in the classroom and what they are able to do with this position. It is also important that instructors acknowledge their experiences, identities, and privileges as they intersect with and impact others. By understanding one’s position, using proactive practices to avoid burdening students of color, and productively handling missteps in class, instructors can take an active role in avoiding harm and creating a safe learning space for all students.

Relations of power within instruction—at once gratuitous and reversible—are a central theme in Brendan Fernandes's performance Foe (2008), which takes its title from a novel of the same name by the South African writer J.M. Coetzee. In the video that records this performance, Fernandes, whose work explores cultural displacement, migration, and queerness, attempts to recite a passage from Coetzee's novel in which the character Robinson Crusoe explains how the tongue of Friday (the so-called "savage" helper of Daniel Defoe's novel) has been cut out, leaving him unable to speak. For this performance, Fernandes hired an acting coach who he tasked with interrupting his recital to provide him with live instructions on how to speak in the proper accents of "his" cultural backgrounds.

Practices

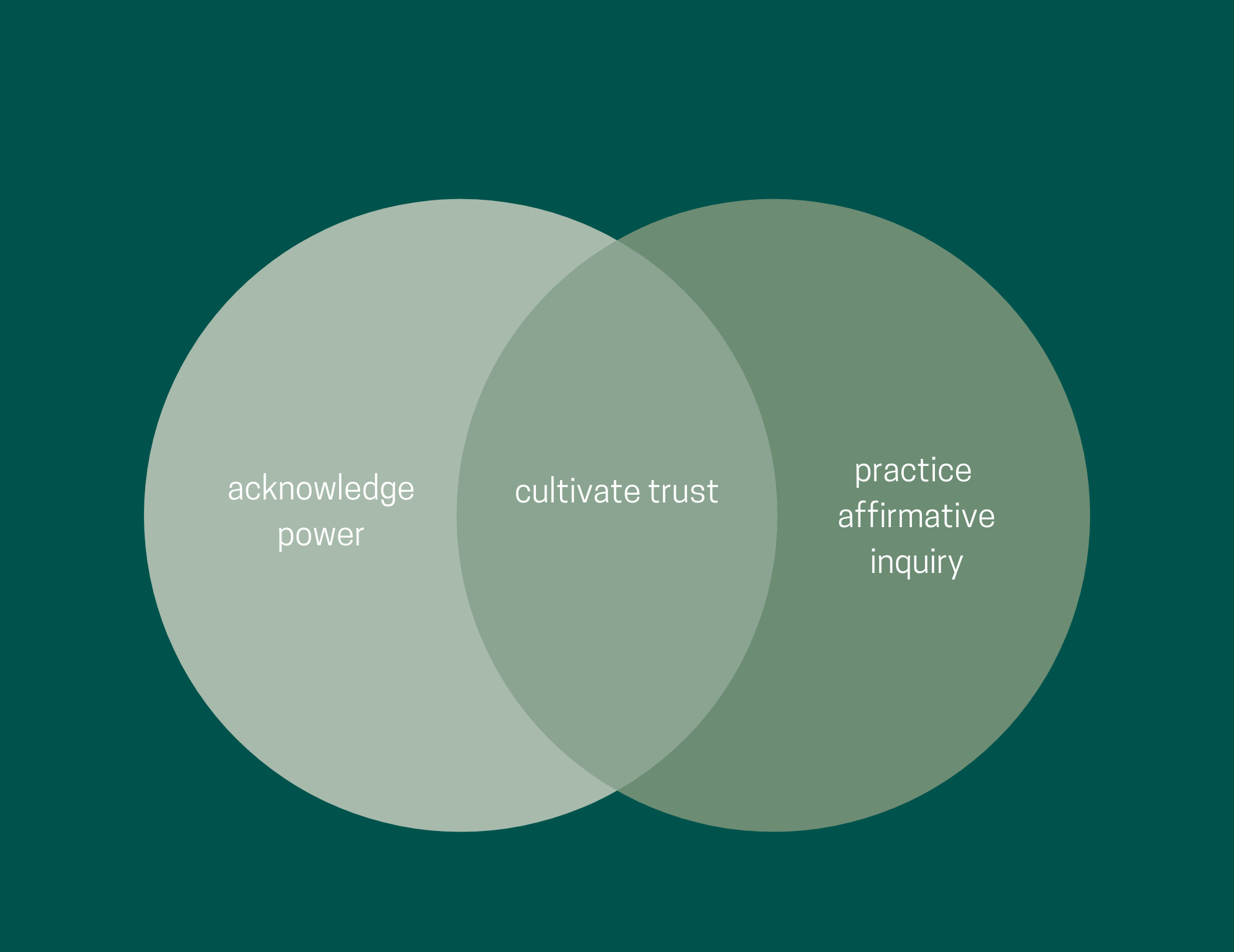

As an instructor, it is important to understand your position of power in the classroom and acknowledge your experiences, placement, identities, and privileges as they intersect with and impact others in the classroom. If it can contribute to the learning experience or cultivate trust between you and the participants in your class, sharing your experience and how it informs your approach to the class content, as well as being honest about your privileges and powers, can allow you to position yourself within the learning environment and not above it or your students. Sharing your experience with your students can also serve as a model for how they can account for their own privileges. It is especially important for white instructors who are establishing relationships of trust with their students to spend time early in the semester acknowledging the ways they understand their whiteness in relation to the subjects they teach. At a minimum, doing so can help students of color feel more comfortable within the classroom. But also, by reflecting openly on the privileges that whiteness affords, as well as how one’s intellectual and political commitments take shape in the light of this knowledge, can usefully demonstrate what engaged pedagogy looks like. More broadly, is equally important to be actively anti-racist as one’s own biases, especially when left unchecked, will affect how students of color and Black students engage with a class. An instructor who is white, which is most instructors, and not actively anti-racist, can potentially create a hostile environment for students of color that will not be conducive to their learning. It is therefore imperative for an instructor to acknowledge their power and privileges, and to be clear about how those powers and privileges inform how they engage with the material they teach, in order to create a brave and trust-filled learning environment for all students.

In the teaching process, it is important to acknowledge the fact that each student has a unique identity and relationship to the class content. In order to avoid burdening students of color with becoming “teachers” to their classmates, instructors must become aware of harmful inquiry practices and work to mitigate them by cultivating affirming inquiry practices. Affirming inquiry practices involve mutual risk-taking and vulnerability among all participants, shared and mutual responsibility for contributions, and lastly, mutual benefit from discussions (9-10). Inquiry practices that are affirmative include ones that encourage contributions from all students and that model ways of being in dialogue that encourage bravery, validate risk, and take responsibility for contributing to what is being learned.

Harmful inquiry practices are ones that place the burden of sharing on specific groups of people or that demand their contributions without offering anything in return. Fisher and Petryk describe two examples of harmful inquiry practices that are very common in dialogue spaces: the first is “experience parasitism,” which occurs when “the vitality and dynamism, the life of the dialogue, is dependent on one individual or set of individuals sharing their experiences” while others sit back and listen; and the second is “cultural strip-mining,” which occurs when a resource of one group (often a marginalized one) is identified and drawn out for the educational benefit of more privileged participants (11). As Fisher and Petryk suggest, these inquiry practices can cause individuals to take on an uneven responsibility for making contributions to the discussion—a dynamic that is especially likely to make marginalized students feel that they are obligated to share information or experiences, but that they will not be given the opportunity to learn anything from their peers. The harm of these practices is an effect of the teacher’s failure to facilitate a learning environment that allows all participants to practice reciprocity and vulnerability, and to contribute equitably to the learning process.

One practical step in avoiding harmful inquiry practices is to consider the way student participation is valued in the classroom, especially as it pertains to a student’s grade. Having in-class participation count for a large portion of the student’s overall grade in the course may exacerbate the burden that students of color feel to teach others in order to participate in class conversations. In classes where participation is necessarily a large part of the grade (like seminars), instructors should add a clause in the syllabus and announce during class that students are not expected or required to share their trauma or personal experiences in order to fulfill the participation requirements of the course. As other parts of this resource suggest, a collaboratively produced community guidelines document might serve as a helpful resource and exercise for students and the instructor to set expectations for participation and to encourage everyone to become accountable for engaging in affirming inquiry practices. For more on the benefits of community guidelines, see the section on “Student Power and Privilege.”

In cases where students share that they feel harmed by something you have said, done, or allowed in your class, it is crucial to understand how to best react and respond without exploiting your power as an instructor. Relatedly, as other sections of this resource suggest, it is important that instructors do not leave it up to students of color to call attention to and address harmful comments and behaviors in the classroom. If you become aware that you or a student has harmed the learning opportunities of other students or if a student approaches you with a concern, you as the instructor should address it right away, regardless of whether this harm was intentional. As alluded to in the subsection on “Student Power and Privilege,” harms that are not addressed swiftly by the instructor can produce a hostile, uncomfortable, and burdensome learning environment for concerned students, making it difficult for them to learn and thrive. Additionally, it is easy for instructors to overcompensate when harms or mistakes occur in the classroom. Too often we have seen that when instructors feel that their power and privilege are threatened, they act in harsh and defensive ways toward students of color. Instructors, especially those who are white, should instead pause to reflect and consider student concerns. It is not necessary to go on a power trip in order to prove that you are correct and, in the process, disregard the feelings of any student.

Practicing vulnerability by openly acknowledging a mistake is an important first step in rebuilding trust and community within the classroom. It can be helpful to pause, acknowledge the harm, center the needs of the people who were harmed, and then address tangible steps the class will take to move forward and prevent future transgressions of the learning community. Additionally, it is important that, when you acknowledge harm, you don't excessively apologize and put the burden back on students of color to console you by saying “it’s okay.” Instead strive to address the issue and prevent future harm for students of color.

Reflective Questions

For faculty

In what ways can cultivating vulnerability contribute to a more empowered, engaged, and thoughtful classroom environment? How can I be more proactive about acknowledging harm done within my classroom?

For students

If you are a student with an empowered identity or set of identities, how can you use this power to avoid burdening marginalized students with serving as your instructor?