Set design and hand intelligence

It was funny in the context of the Fall 2020 semester that my book Fixation was published in September, which is all about physical objects. The book is all about really seeing and understanding objects around us, working with your hands… all these things that of course we're still doing since we have surroundings. But as the New Yorker cover that came out recently showed us, there’s a frame, and then there's the reality, and we're not, when we’re stuck in a digital world, dealing with the reality.

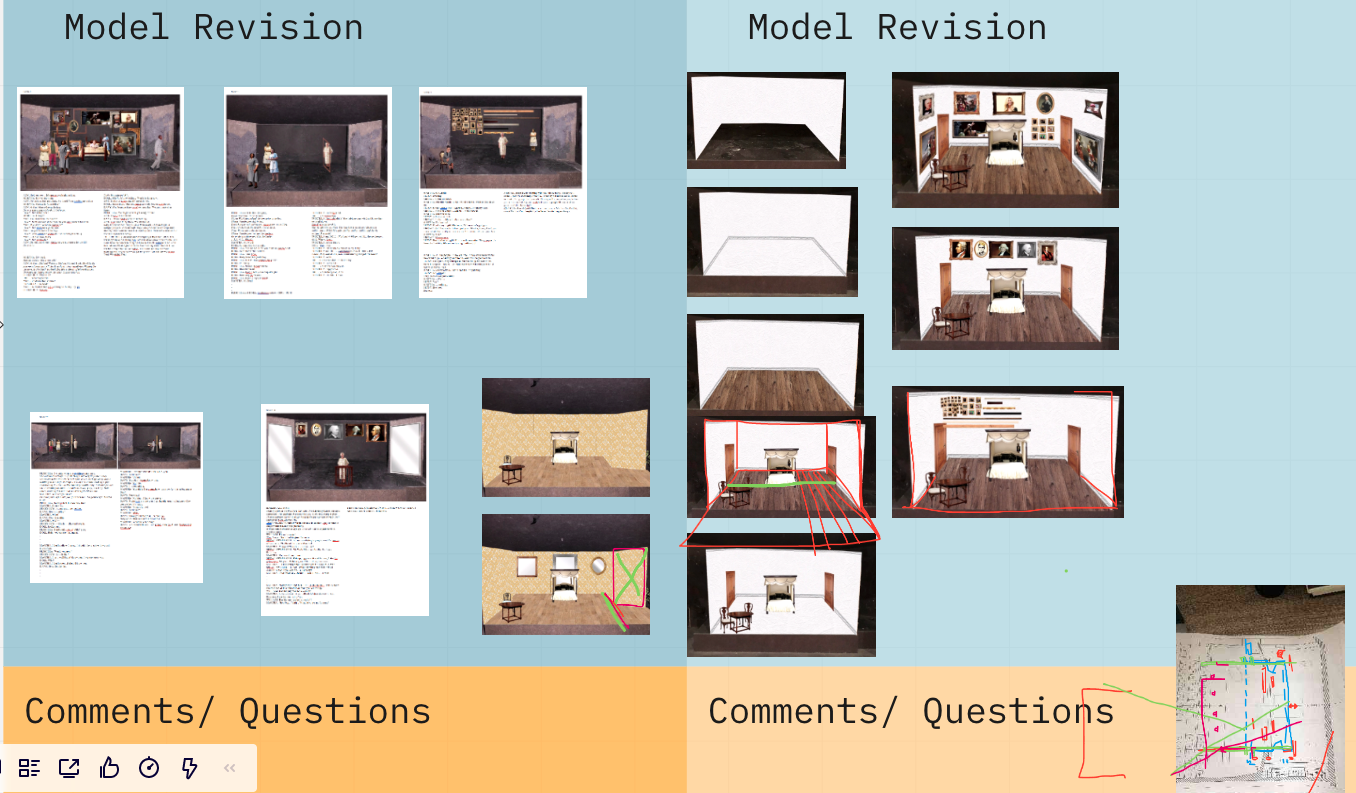

The course I taught in the Fall 2020 semester is called Set Design; it's an introduction to designing for the stage. It's a studio course where students do visual research, analyze texts, sketch, build models, and usually do some drafting. In the normal world, it's very embodied. The end product of a real world set design is a show on stage that has a physical set with actors. In our class, the physical product at the end is a three dimensional model with some digital materials surrounding it, like a digital rendering.

Even before the pandemic, we were always moving between 2D and 3D, between the digital and the physical. The problem with the pandemic is that the balance got way off in terms of the capacity to do certain things that we do in real life. When we talk about commonly used building materials, for example, I used to have a little box of all different materials that the students could actually touch and look at, so that when we're talking about the properties of steel, or aluminum, versus wood, or certain types of fabrics, they can actually hold and look at materials, as opposed to looking at pictures of them on a screen. This year, I sent [students] some materials to start, because usually I have them build a scale model of the actual theater, and then you work within that. But I didn't want to have them struggle to build that all by themselves and find the materials. And I try to reuse everything anyway, so I didn't want them buying all those materials. So I sent them the model boxes that we had, and I sent them a scale ruler, and I sent them some printed out drawings of the space. It was such a simple little thing. But I think it was pretty important.

Often in my class, I feel like trying to reconnect my students with some other forms of intelligence, forms that are very strongly rooted in the visual and in the embodied. My students come into my class very prepared to read and talk and write. It’s very, very easy for them. And for some of them, it's harder to communicate, for example, through images, or communicate through three dimensional spaces or understand how an object or body might move through space, and how you can actually speak with that. So now I've also added a whole bunch of units about the materials themselves in terms of what they're made of and how a tree grows so that you can make a pine stick from it, and what the impact is, on the people who make the objects or materials we choose and what the impact is on the on the earth itself of choosing steel versus aluminum versus wood versus cotton.

And all of it is some part of an attempt to help them flex that muscle that I do feel like our society has a little bit de-emphasized: the ability to, to speak with images, the ability to understand the knowledge of the body, of the physical objects and materials around us. That knowledge, in the first part of the class, comes from modelmaking: what does it mean to cut something out neatly, and to make it stand up and to glue it together and use your hands to say something? And they feel very awkward, because [the students’] hands aren't any good yet, and they come out all crooked, and the cuts are all messed up. And so the thing that they make isn't quite saying what they want it to say yet: because they don't have the skill, they don't have the capacity in their hands. Digital tools can help with that, because you sometimes can do things in Photoshop that you can't do in modelmaking if you're a novice, or that would take you six hours in the model. But that muscle of the hand maybe didn't get quite as much exercise this semester as it does in other semesters, because [students] leaned more on the Miro board and on Photoshop. We did all digital drafting instead, no handcrafting. There's that hand intelligence that they maybe didn't quite get as much.

Miro

[When we went virtual], I wound up using a Miro Board. It’s basically like a giant wall. You can zoom in for anything, and you can have links. I'm probably going to use [Miro] in the future– it is a good enough substitute for printing. I won't go back for two reasons: to save the printing, and also because then you do have a really nice record of it. Miro is so liberating for teaching, but also for tons of projects. You can really work together in a way that feels like working together in a room, in a workshop setting. So some of that will definitely stay. But given that the work I do and teach is still really rooted in making objects again, it will be interesting to fold that back in.

The materiality of the digital and consumption

I think [the materiality of the internet] is a hidden, unspoken thing. We're all moving forward as if all of our actions writ large have no impact, but at least some of our actions– food and consumption and air travel– at least we kind of know that they have an impact, and we're beginning to talk about it. But the impact of all of our digital life is very rarely spoken of, and the vast amount of energy that it takes to store all of our images and all of our Snapchats and all of our Facebook videos, and even our Miro boards for class - there is an impact to that. The sustainability department at Barnard has not yet even begun to kind of talk about it or calculate it. So it's kind of a big crazy question mark for right now.

I still think that the impact from creating physical objects is so significant that there is some benefit to putting things up on a Miro board instead of printing them all out or whatever. But I think it comes back to a deeper question about the scale and excess of human activity, because you start to feel really helpless. You're like, “Oh my god, I can't even do things digitally? Now that’s trashing the planet too?!” But then you come face to face with a really hard reality that everything we do has an impact: every single thing we do. Even digital things that feel like nothing, there is a real world energy and material support. And that support is really vast.

With my work on consumption, I'm trying to help people to understand that every time they buy a phone or a lamp or a chair, that threads back to this incredibly vast infrastructure of production. And I guess every digital action threads back to this incredible vast infrastructure of servers, then energy. That's when it gets scary, because you realize everything we do is supported in this way. The scariest part about it is that very little of what we do circles back to support that system, right? This is the crux of the problem. If I buy a phone, there's a huge amount of resources and energy that go into that phone. When I'm done with it, very little of that energy or those resources is recaptured. Even the food that I eat: we don't capture our waste and feed it back into the cycle. When we die, our bodies aren't even really consumed by other organisms, because we embalm ourselves or put ourselves in boxes.

And the same thing with our digital materials. None of those actions are looping back into anything. And that is what is so crazy when you stop to think about it, and when you really can come up against this hard wall of like, “Oh, my God, I don't know what to do.” Except that of course, the answer is right there in front of you, which is somehow we can bend back those resources and use our power to do that. We have the capacity to build this incredible logistic linear system, and we have the capacity to build that digital world; therefore, we should have the capacity to bend it and have those resources loop back in, even if it means really radical things like recapturing every nutrient, 100% renewables for those servers, recapturing every mineral that goes into every object and goes into our bodies and into our refrigerators– recapturing all of those nutrients and feeding them back in somehow.

It’s just like the physical world and it's connected. There’s the digital world, the labor, the cost, the resources to manage that. And then there's literally the physical objects that connect us to the digital world: the headphones, the computer, the WiFi router, the FiOS cable. So all of that transition between digital to physical, shows us that they're not actually– it's kind of like my class– they're not actually so separate and different. We just toggle between them.

Do we need to build a system where they degrade and disappear after a certain amount of time, or where we have to choose: kind of like a suitcase in which you choose the amount of materials you actually can keep? Weirdly enough, I think we're actually moving forward with the digital world just the way we did with the physical world. We’re viewing it as an unlimited resource. We're assuming that every picture of my kid eating Cheerios is so adorable and it can be kept forever and ever and ever. Every set design project, there's unlimited storage. Maybe there is or maybe there isn't. But it feels clear to me that the attitude we're approaching the digital with is the same attitude we had historically with natural resources: that they were unlimited and linear. I don't know enough about storage to know whether that's true or not. The little that I've read about it makes me feel that probably it's not going to work out in the long run.