The materiality and subjectivity of the digital

I think one of the defaults is to think of the digital as a medium or something that content passes through. And sometimes there's also this understanding of technology as being neutral. And those are two things that we're really working to push back against. So thinking about the technology, it is definitely not neutral and it’s very material. When we talk about the digital being material, we're trying to be clear about the bodily impacts of the technology on us. This has a lot to do with accessibility for one thing, but it also has to do with neck pain, and the way that our bodies are changing in response to how we're living our lives digitally. And, of course, the materiality of the internet that connects us and the hardware that we need in order to communicate and that we're using in order to communicate that is absolutely material comes from extraction, mineral extraction in areas that politically have been destabilized by the US government. [Those minerals] are put into factories that often have unsafe working conditions for the workers. They use toxic chemicals and flame retardants and things like that and then when we receive them, we use them for a short number of years, and then they're recycled into e-waste. And e-waste is often exported to other countries. Then the hardware is deconstructed to extract it again for valuable materials, and the extraction process releases toxic chemicals into those environments and into the bodies of the workers who are doing that work.

One of the major changes with the pandemic has been that there's been a massive increase in internet usage over the last year. And that's had an impact right on how much data is being processed in data centers, and how much heat that is being emitted and how much cooling is needed in order to keep that heat within whatever parameters different governments have set up. And teaching has been a part of that impact for sure. One other really material change has been the way our bodies have been exposed to harm through technologies like Zoom, which was unencrypted. I was at several events at the beginning of the pandemic that were raided. It's not that the classroom is necessarily an entirely safe space, but that was a different kind of exposure, that has bodily impacts that can create trauma and expose students and instructors and facilitators. And it's trauma piled on top of the trauma of the pandemic as well.

Emergent strategy and right relationship

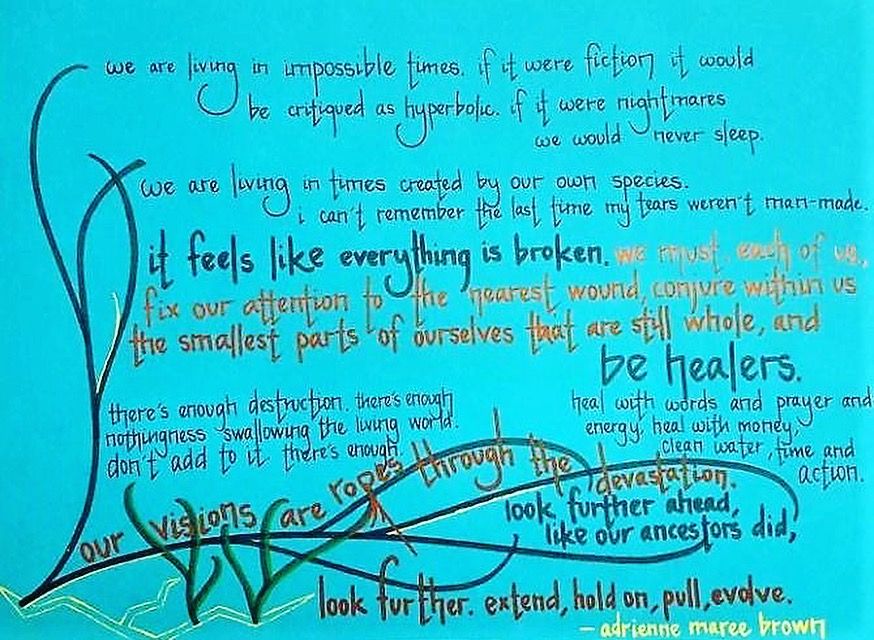

I've been trying to really think about ways to frame things that we can do that don't frame what we're doing as individual responsibility. It's not our fault that corporations are creating data centers in these ways and requiring email as a way of participating in work and school. That’s where adrienne maree brown’s emergent strategy framework comes into play for us in thinking about small things we can do to be in right relationship with the world around us including the environment, and understanding ourselves as part of that environment, of course, not as something separate. For me, I think about the way I want to be in the world. The way I want to be in the world is not full of shame and guilt and is not paralyzed by those feelings. And so this is a personal thing, too. I’m trying to bring in forgiving ourselves for making certain things. And part of the ethics of care is caring for ourselves in this moment.

Meditation, connectivity, connections

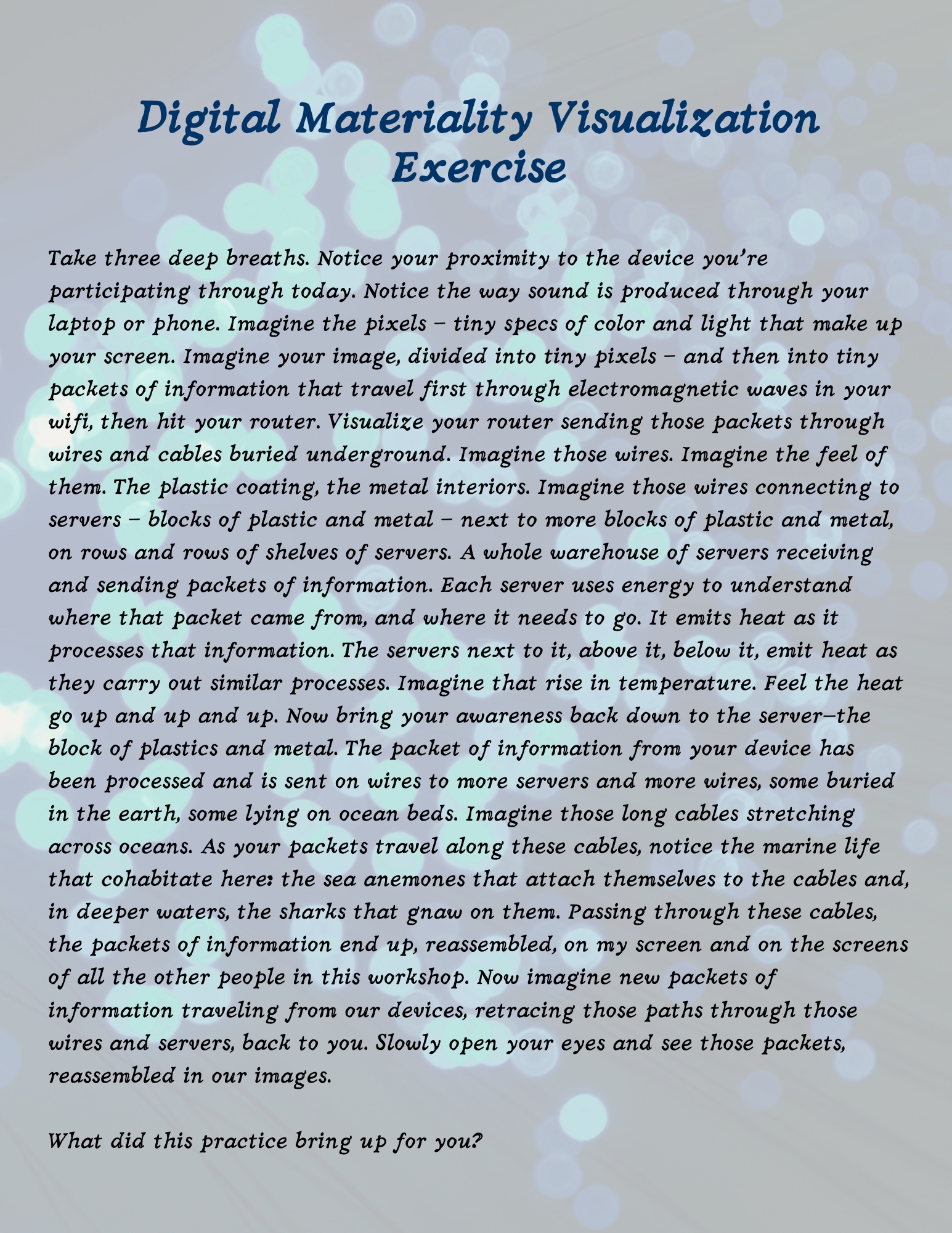

I've been growing more mindfulness and meditation practices in my own life as well over the last few years, inconsistently but powerfully. They’re really effective for me. For the Reducing Your Digital Carbon Footprint Workshop I wrote a visualization exercise to understand the way that we're connected through especially wires and cables and data centers and really what visualizing information traveling through those things from me to you might look and feel like. I have to say it was an incredibly vulnerable thing for me to do. I think really acknowledging our bodies in relation to our digital lives is just incredibly important. And important in thinking about technology not being neutral is thinking critically about the technologies that we're working with and creating. I think the more we can be in our bodies, as we're thinking about digital technologies, the more we can see what goes wrong when there's a mismatch between what a user interface thinks I should be as a human and what I am. That opens up some creative possibilities for, as adrienne maree brown says, imagining the liberatory worlds we long for—creating and imagining those. I really do think meditation is an important part of that.

The DHC’s role

Ana Lam, our Post-Bacc at the DHC is really great about helping students understand images. A lot of the tools that students are using require images to be included in some way. And oftentimes, the way we do that is we go to Google, we search for an image, we download it and we upload it back up. So there's a lot of doubling storage that's living somewhere. We talk to students a little bit sometimes about Cloud storage, and what we've created that we don't use anymore, that needs to be deleted, and the practice of maybe not creating extra copies of things online. Ana has been really good at helping students connect the image from a URL - helping them understand how to get the image link, and then how to use that. Sometimes we also then talk to them about permalinks, or things that they can do, like the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine where you can capture websites and get a permanent link to that capture. We talk to students about storage not being infinite, that it continues to expand and more data centers are created and we talk about how to be mindful and try and delete things we are not using like email - unsubscribing from lists, for example. We have not yet got to the point where we're talking with students about the ecological impacts of their digital projects. We're doing this with faculty and staff as part of our consultation process. We have a project charter that we use when we're working with faculty and staff on projects that asks, “What are the ecological impacts of this project? And how are we going to mitigate them?”

The idea is that for every project that comes up, we default to Jekyll, a static site generator. Unless there's a decision that we need more functionality beyond our development capacities at the time, whether that's time or experience. So then we use a tool, like WordPress, or Omeka or Scalar.

I think some of the work we're doing is newer to digital humanities as a field: thinking about the environment, analyzing the environment. The environmental humanities are becoming part of the digital humanities. But thinking about the digital footprint of what we're creating as digital humanists I think is new.

Bethany Nowviskie’s “Digital Humanities in the Anthropocene” was really pivotal for me as a person thinking about all of this. And then I think for a lot of digital humanities, there's no book on this - it’s to be written, I think, there are definitely conversations about sustainability and digital humanities but they tend to be about labor, which I think is a really important part of sustainability. They are usually about how we keep a project on the web for as long as possible, or for as long as it needs to be. This is something we're still kind of working on and thinking about how to reframe so it's more within an ethics of care. But when can we shut something down? When has a project lived its full digital life, and we can celebrate it, and then we can remove it right from the web, or archive it in a particular way? And not keep it up forever. I think it’s important to flip the discourse, from “How can we keep this alive for as long as possible?” to “When has this thing lived its full life?”

Accessibility is definitely part of our pedagogical practice. One of the practices that I do for my workshops often is giving people the link to the slides at the very beginning of the presentation. Oftentimes people have assistive technologies on their devices so that they can then apply those to the slides and make whatever kind of transformations they need and then better experience the workshop. Kaiama Glover, the Faculty Director of the DHC and I were just talking about the fact that the inequalities that existed before the pandemic, and before the move to digital and online teaching, absolutely existed. And in some ways, some of those things have been exacerbated, and some of those things have been relieved through digital technologies. I think being mindful of the way that our bodies are different and how technologies are created to center certain kinds of bodies and experiences and exclude others is really important. We teach a lot from the work of Ruha Benjamin and Sasha Costanza-Chock when we help students develop frames for thinking critically about technology.

Proctoring software is one of the biggest things that has come out of the pandemic. And so again thinking about accessibility, I’m thinking about how some of the initial facial recognition software wasn't good for Black and brown skin, darker skin. And it wasn't good for people with ADHD who move their head a lot. I don't know if anyone else is talking about that in the [pedagogical] context. If they are, great. If not, I think that needs to be a part of the conversation too, about the way that technologies are used to surveil students in online classrooms sometimes.

At the DHC, we have been thinking a lot about a Fellowship Program, what that's going to look like and who that's going to be for. We're wanting to design something that really uplifts work that brings together Black feminist practice and environmental sustainability or environmental justice and thinks about the digital, and have created a brand new circulating collection of books, housed in the DHC, that connect these three spheres that we hope will be available for browsing and borrowing in the fall. We're also working on building out a digital carbon footprint calculator. So watch this space!