Designing Design and Buoyancy

Designing Design was originally a course taught as a very traditional graphic design course. Part of the course is about space, and my deep belief that the way our environment is made shapes us. It shapes not just the way we behave, but also the way that we relate to other people, things and the world.

In Designing Design, we're looking at these places that we inhabit - for example, our classroom. I really like the Zoom classroom because I dislike the seminar classroom. I love that the students are in seminar classrooms physically, of course - that's much better than being online. But what I don't like about the seminar classroom is that if we accept that environments have systems of value and shape people into their future selves. Look at a seminar classroom at Barnard. We see a table, which is a boardroom table, we see very ergonomic chairs set around as if for a meeting, a podium, a projector, and maybe one wall of windows, if that. It's like a corporate boardroom. So what we are in the end preparing our students for is to take part in large corporations that already have value systems embedded in themselves.

Our ultimate goal in Designing Design and in my seminar Buoyancy is to have something made by students which can be traded. For the first Buoyancy seminar, we made an apron uniform that fits any size. We wanted to work on a project about apparel because the textile industry is probably one of the most problematic on earth - and we wanted to think about not “just in time production” but also return to the time when we all made our own clothes and when every pattern was wasteless, because no one wasted anything when they made something. We all made this apron and wore it in class. This was a good way to connect people to the act of making instead of having it be this abstract, alienating object that arrives at your doorstep, that you're free to trash at any time, because you didn't make it and you don't know who has. When students make something, they care about who they give it to and who they make it with. And that's important.

These are very simple means to understand what alienation is, and what it brings. I don't believe that work can be bought, for example. So we talk about it in class because our environment in the classroom is corporate. And the first thing we do when we go into a classroom space, we try to adorn it. For Buoyancy we bought double-sided golden and silver emergency blankets, which are really nothing but cellophane. We would stretch those out on the wall and would create almost a kind of a living room, a place that we're all comfortable in, that we can dismantle in a second.

The first 10 minutes of class is always this kind of construction. Sometimes, people bring different things to the room. It’s just important because if we believe that the environment is important, that it shapes the way we think and behave, then maybe we should think about the environment that we teach in.

What we create in the class first is a studio, because a studio is such a generous structure. It's a place that artists have made for the world. It has to offer this model to all disciplines. It's open. It's not like a lab, which is hermetically sealed, and has to repeat results. It's a place where you can fully let go of control of yourself to learn something about yourself. And it's the frame that allows that to happen. And rigorous testing happens in this sense. And we don't even think about failure in this space. Because failure is also a fully fucked up construct.

For me, the most important thing is this idea: an environment which creates not happy feelings, but actually what labor is, what work is, and I don't think anybody really answers this question. You have a whole world of Marxist communist thought which tries to think of it as something common, something that cannot be monetized, but takes it away from the idea of an individual. Then you have capitalism, which tries to create a commodity out of it. Both ways have failed; there's something deeply flawed in both. And because there is no answer to this question, perhaps work is an answer to another question: What is meaning? What is meaningful work?

I think this inability to distinguish between the state of work and the state of leisure, and no space in this kind of surveillance, all the time work economy, for a social life outside of work is something we're trying to work through with the students. When they make projects, we think about how to make an environment that's both an economy and a great place to be and live. We think about how to make an environment where you live in your work - you know, live there, not die there - not want to escape from there!

Sustainable design/Design as archive

The point of communal efforts and common tasks was to end the mechanization of labor and was to work less - not to work less and be on the street, but to work less and be able to do whatever you want, to create. The artist and furniture designer Enzo Mari is someone we look at in my courses, and he talks about this community, this society of artisans, people deeply involved in making things that last or making things that have meaning for other people, not necessarily material things. I think our relationship to material things has to change, because we look at the world and other people and other people's labor as disposable raw material. And if you look at it as that, you dispose of everything.

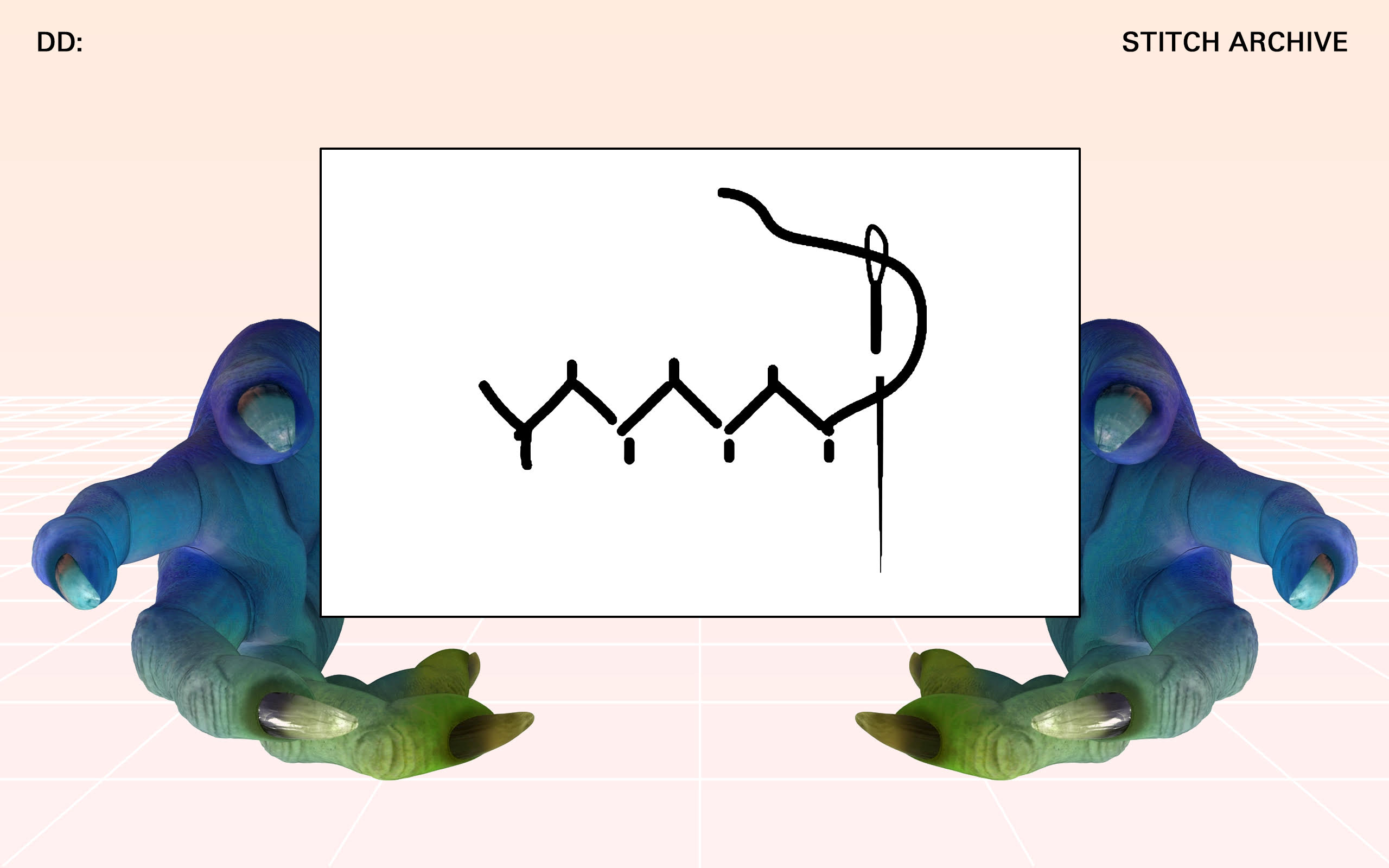

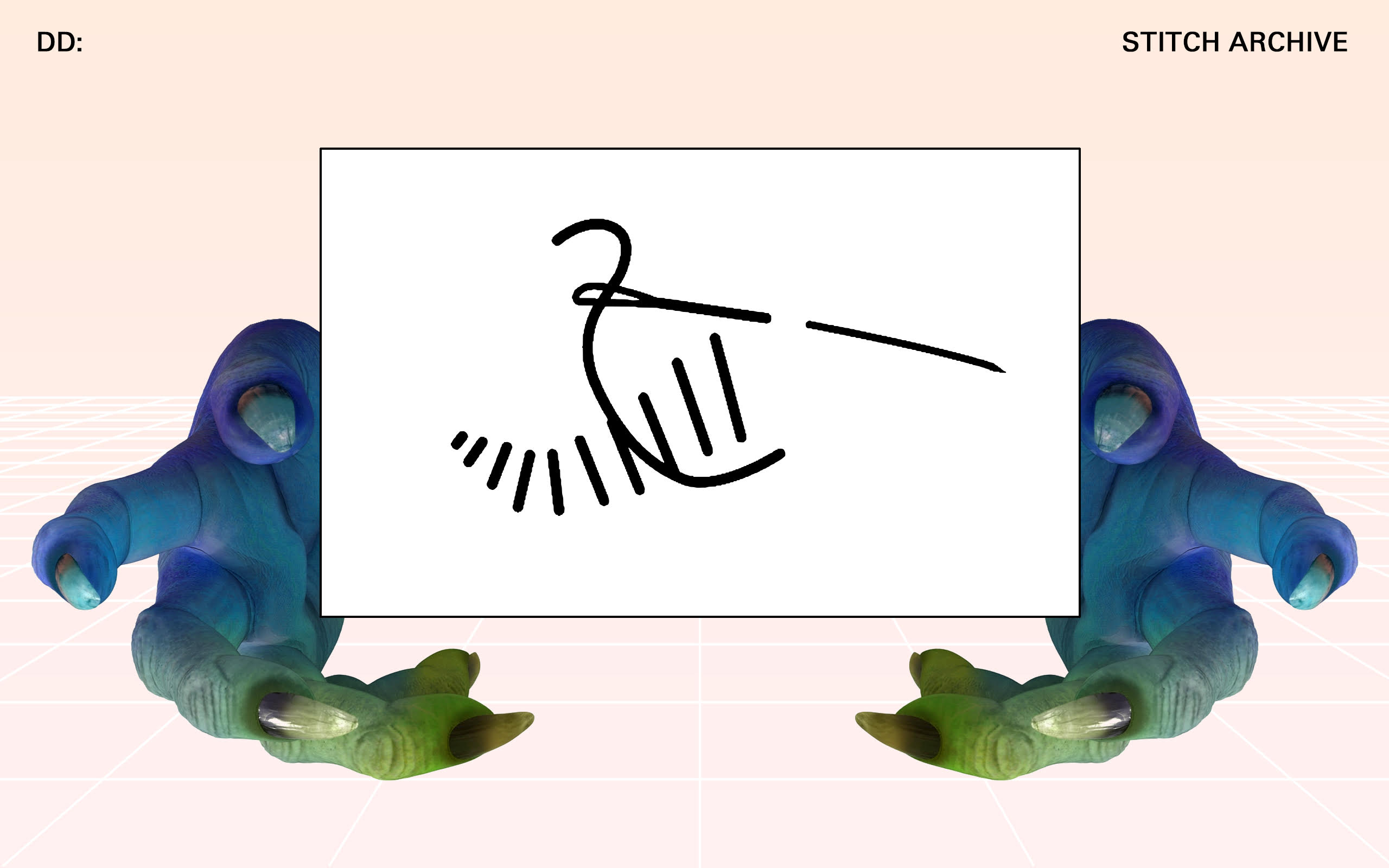

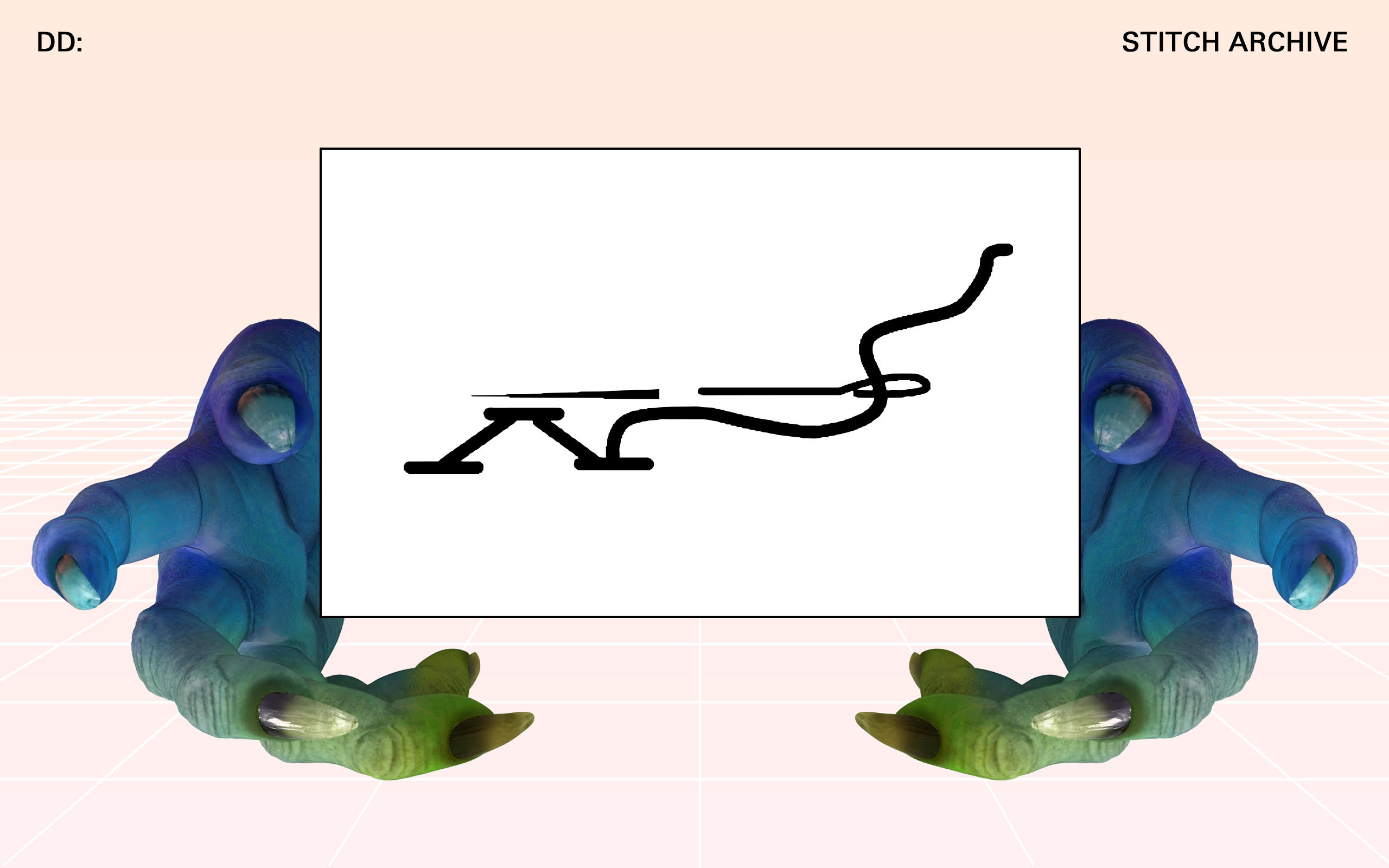

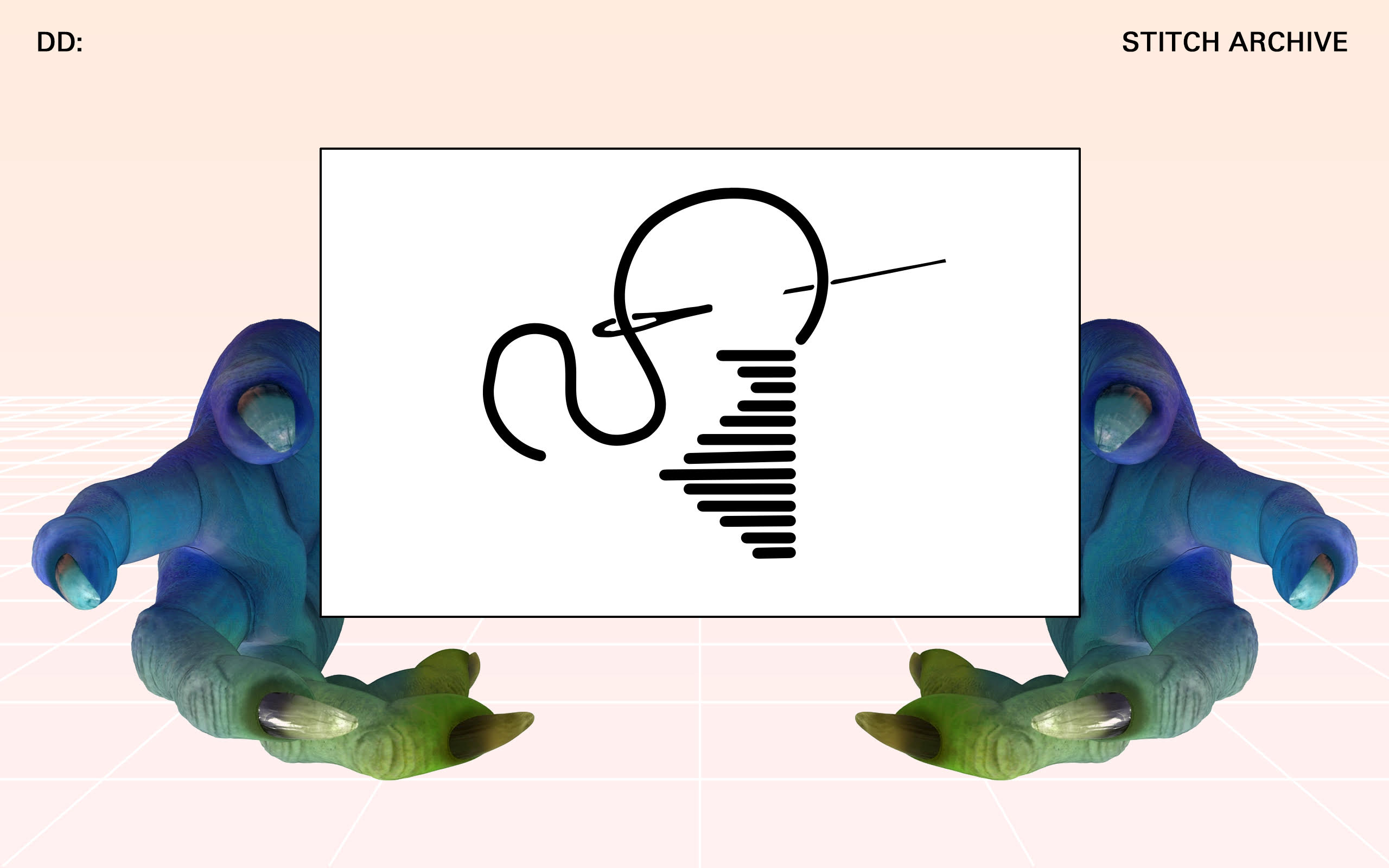

With students, I think one of the exercises that was most fun, for me, at least, was related to a study abroad program I’m organizing with the Athens School of Art. There I found the Museum of Greek Folk Art. They have an archive of costumes. And those costumes had many stitches, and ways of embroidery that are completely lost, and undocumented. And in the Designing Design class, for example, we were creating a garment with these lost patterns. In the class, we're trying to think about apparel, not as collections, but actually coming back to a time when people made their own clothes and did not waste because they had to weave their own material. So each person in the class created one pattern that wastes zero material. And then to embellish the materials, everybody adopted one of the stitches. The point was, "This stitch is dead if it’s not practiced. So why don’t you become the person who becomes the container for this and you teach it to your mom, to your dad, to your friends? You will become the ambassador for this and you are the living embodiment of this memory by creating it, by repeating it, by teaching others." So it's not dead - it's like a language that you have preserved.

It's also great to feel the speed of labor in your hand, as you're pushing the needle through the fabric to create a shape and feel the presence of those who are no longer here and preserve them for those who are coming. It's not just an exercise in that specific stitch - it's also a way to treat things. What's beautiful about that course is that we have five groups and each group has five members, and they become a studio themselves.

I demand a lot in my courses because I think I also want to learn too. The reason I teach is because I'm not done learning. And I'm very interested in what young people have on their minds, what are their problems, what they think, operate against them, what they think they need to solve, and help them frame those things for themselves. I don't think for this generation there can be this promise of a house and a family - it's impossible. There is no security. I don't come from a secure place. Definitely. So I've always adopted this idea that “I might as well do what I like, because I'm not going to get that, ever.” So happiness and enterprise have to come somehow from the idea of being comfortable with yourself and others around you - because there are a lot of others around us, especially in New York - and encourage that.

I think critical thinking and analysis bring a lot of this world and there are primary models in the way people learn these days and have been learning, but I think they only go so far. The idea that imagination has to be exercised, like you exercise muscles, to be able to work within the framework that you're given but still feel free - that’s the secret to anything!

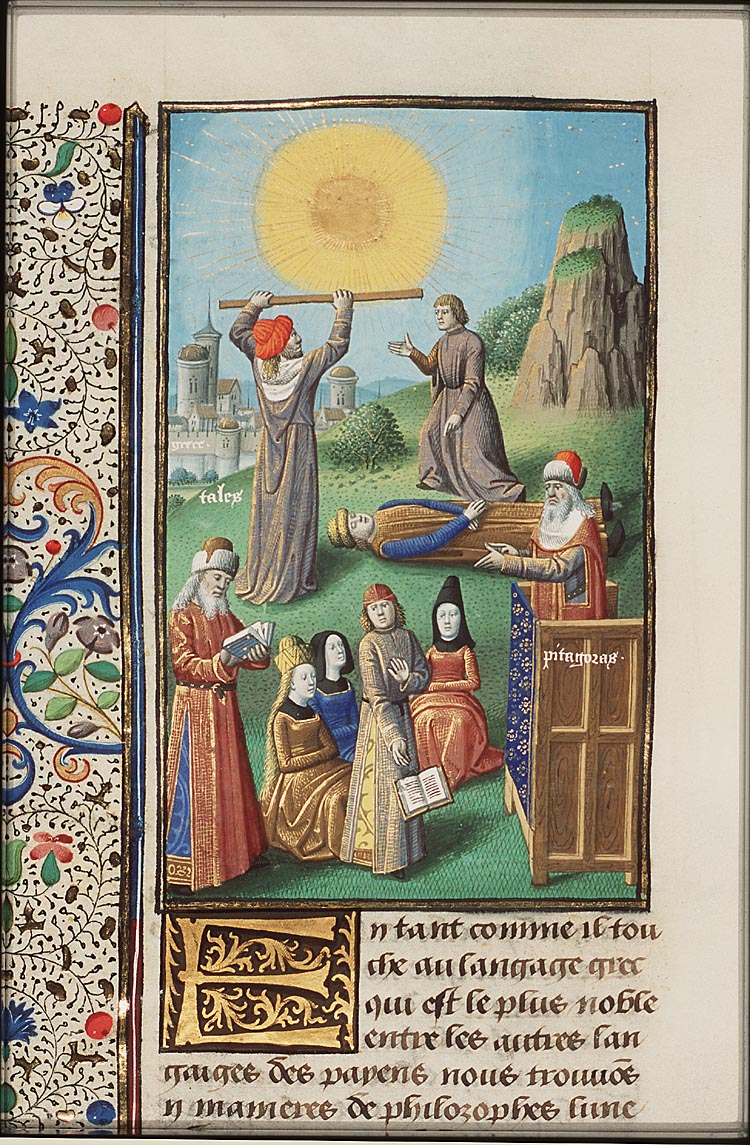

One of the most interesting speakers I've ever had in my class is Mladen Dolar. He's great. He wrote A Voice and Nothing More in which he talks about the first Greek schools like the Pythagorean School, where the students would sit outside and with a kind of a panorama in front of the students almost like a curtain. And then the teacher would speak from the other side. And all he would hear is the voices of the students and all the students would hear the voices of the teacher. And this is the way that knowledge was transmitted. There’s the idea that we must be immobilized when we’re learning because it’s preparation for sitting for the rest of your life. As soon as the Barnard lawn is available, we need to start exercising and reconnecting to the body.

The role and relevance of art and artists: imagination and images

I come from a place where orality plays a huge role. So I try with the students first to think about - and it's so ironic in this fully screen-based optical environment to be talking about - how to construct an image that does not in the end lead to what screens lead to.

If we look at Western canonical painting, we can see why we are stuck in this desire to annihilate the world and ourselves within it. Art is a great place to occupy if one wants to get to our motivations because it is a field that creates desires. So we have to look at how we desire and how we learn desire in the West, and that is through images. And if we look at canonical paintings, for example, Dutch still life paintings - you have these beautiful still lives which are everywhere else called “dead nature.” And each object: salt, pineapple, lobster, silver, glass - is a very scarce item related to a kind of bloody trade route, which is achieved through a kind of major colonial death effort - going to other places and taking from others. These places are created as endless resources for depleting the place that is the object of colonial infrastructure and desire at the same time. And this is the way the advertising image and many of the media images still operate. I try to look at them with students on the most fundamental level, not to look at them how we are taught to look at them, but actually to look at them as pictures.

Our entire Descartian world and Enlightenment - which our educational system unfortunately is based on - is the idea of mapping the world, imaging the world which kind of culminates not in our Google Maps so that we can go from one street to another. It culminates in drone warfare where you can kill anybody because the mass of the map is so precise, and you don't kill them in person in a super abstract death. You kill them by blinking your eyelids through a pair of glasses specially designed for that.

I really believe that artists are here to not just become a carrier for desires that have already brought us here. I like to think about art as having the power to create new desires consciously, in many ways, and in all sizes, from all kinds of fields and groups, because it can now be anything. And that's terrifying to students. But actually, what's great about it is that it can be anything.