Hana:

Could you describe how you engage with the material in your own work as a scholar and what the material has afforded you access to?

Vani:

If I'm thinking about my work as a librarian, it’s obvious to start with the book. A book can be a tool that is used to set certain things in motion. In a larger social sense, books are used from everything from institutionalized religion to what the book symbolizes in government and governance. One of my memorable projects from library school was an indexing project where I found this book called The Magic Lantern, a history of photography. I went through page by page and manually took notes, where I was looking for themes and keywords, and my project was to create an index for it. And now I'm like, “Whoa, actually maybe that's something to bring back in my teaching or work with students because there's so much - it's really this pretty powerful way to engage with meaning making that is so analog.”

I even think about the page. In poetry, poets do fascinating things with pages where you can have a blank page or a page that feels like art, a rupture or a portal into a totally different world. There are also book forms that are less hegemonic in our particular time and social context, but may have been important in other contexts, like scrolls, for instance. But scrolls are also digital now. That experience of scrolling through what feels like a potentially endless stream of text is, in a digital sense, very relevant to now. So the relationship between books and the digital, and those visual and touch aspects are especially important in my own personal work.

Hana:

Could you discuss your relationship to ceramics?

Vani:

I think one of the most amazing things is that ceramics is a chance to do something that is such a departure from the screen and from the digital world, but so digital in that literal sense of using your fingers and your hands. I also love the idea that you can make something by taking away from it. With pottery on the wheel, you're literally creating by taking matter away, and I just found that process to be really fun, almost like a haptic analog to editing or revising. I think that's why I love it so much, because I often have a hard time with editing and revising, but it feels so vital.

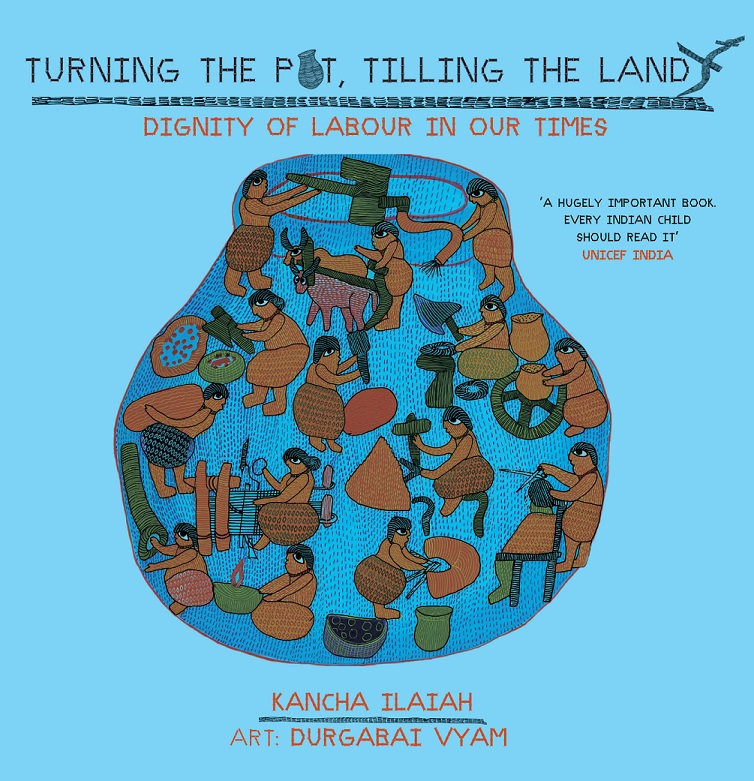

I started to do this big writing project for my MFA program last semester, where I just put together a lot of writings about pottery and started to do even a little bit of research around the significance of pottery in South Asia. I was really interested in the history and politics of what pottery might have meant to my ancestors. The research made me aware of pottery’s relationship to the oppressive and ongoing caste system in India. Historically, the work of potters was not really valued by the dominant culture. And any time I think about materiality, there's so many unanswered questions I have about labor, too. Like, “Where's the clay that we're using coming from? What kinds of labor make that possible? What is the relationship to land? What is the relationship to land and indigeneity and the sourcing of clay?” To bring it back full circle to technology, even the devices we use are recreated by people's hands; it's not like they exist in some space that's outside of that.

Hana:

I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about annotation, indexing, and how you see that intersecting with poetry.

Vani:

I did a research project where I was writing an essay for an anthology on critical race theory in librarianship. I was reading a lot of critical race theory for the writing process. I ended up printing out all these texts and wrote notes on them. I was also using highlighters, and color felt really important - adding these moments of intensity.

I’m going back to a digital image here, thinking about the way people use heat maps for data. Sometimes when I’m reading, there's a moment that feels like it produces a response and I want to mark that on the page some way. It's even less about making meaning but sort of registering an emotion, like, “This made me feel something.”

Hana:

I think that doing things by hand forces us to register information or feelings in a way that sometimes feels squandered by reading a PDF, to me at least. How do you feel like your relationship to the material has changed at all throughout this shift to mostly working online now?

Vani:

I think I realized with some sadness that a lot of the ways that I would have incorporated more embodied teaching practices in person—giving students post it notes to write on to trade with each other where they write down certain ideas, space to write something on a dry erase board, time to go into the stacks to look for physical books—have either been cut out or shifted into work that still technically involves the hands and the body, but not in the same way. Now it’s like, here's a Google Doc, here's where you can write down your keywords. I feel a sense of loss around that, but I think I've defaulted to letting go of these practices because for librarians, our awareness of the material is so often connected to the economic. We literally are responsible for purchasing a lot of the materials that students and the faculty rely on for teaching and learning. A lot of us have been thinking about how unaffordable the textbooks are. I think we're all mostly starting from a place of assuming that a lot of students don’t have print copies of books, so part of it is just the book as an object is missing.

This is such a strange tangent, but I've been thinking about, especially talking with you, how we both use our hands when we talk. There are these meetings about the specific ways that academics use their hands when they're talking, like turning the dial when a paradigm is being shifted. Gesture as a part of meaning making and expression in learning contexts is actually really beautiful and exciting to think about. Growing up, I associated talking with my hands, as, in some ways, this really beautiful trace of my identity because it feels very South Asian to me. I think that it would be cool to explore more around gesture, even if it's just incorporated into an icebreaker - to start out a gathering with, “What is a gesture that conveys how you're feeling about your research right now?”

Hana:

That is such a lovely idea, and makes me think about embodiment. What new types of embodiment is online teaching and learning providing? And what do you think is lost and found in these new ways of being embodied?

Vani:

At one of the librarians’ meetings, we once had an icebreaker to look outside the window and share with us something that you see. It was kind of amazing because everyone's seeing something different: we're not in the same room in the Milstein Center. The reason I’ve hesitated to do something similar with students is because they might not have the same kind of privacy or feel the same comfort in expressing or sharing in an online learning space; they might be in a room with siblings or family or there might be a lot of things going on. That is something that has maybe made me feel hesitant to experiment with certain kinds of embodied learning, but it’s interesting to think about what might be possible.

Hana:

Is there anything else that you want to share about how you engage with the material?

Vani:

For many stretches of time in my childhood, my grandparents would come from India to stay with us. It was a really special time. I have this memory of being about ten years old, and every afternoon, my grandma would be sitting and knitting and watching General Hospital or some other soap opera. I was so fascinated by her knitting that I said, “Please teach me how to knit.” She finally taught me. I would make mini outfits for dolls. Over the years, I’ve been coming back to knitting as a really soothing and creative practice. Right now I'm making a blanket from my friend who actually has COVID right now and it's a really hard time for her, but I'm hoping I can give it to her.

I also love cooking, which just feels like the most regular and necessary and vital and also really fun form of material, embodied practice in my life right now.

Hana:

I feel like we're so in sync; ceramics, knitting, and cooking are all things that I think about a lot, or have done and loved. I really appreciate what you shared.

Vani:

Thank you so much. This is inspiring me to think about going back to my teaching and think more about embodiment. I also want to mention that through folks like Jenna Friedman, the zine librarian, and also the countless people over the years who've done amazing work with the zine collection, I've learned about that very simple but amazing process of making a zine out of one sheet of paper. There are diagrams where that has been shared online. It could be really fun to have the zine be a prompt for students who might be at a juncture in their research and writing process. It could even be a way to create a mini version of a thesis. Let’s say you only had this tiny amount of space, but you wanted each page to represent a part of your thesis.

Hana:

That’s a fascinating exercise in terms of a way to think about organization and structure. I think encapsulating a thesis into zine could be a really useful way of reverse outlining. I love that idea.

Vani:

I haven't actually tried it for myself, but I'd love to. Maybe a final thought is just: I guess we can always try things out ourselves, we can try some of these ideas out in our own lives. And that's fun to think about.