Student Engagement and Community-Building

Student Engagement and Community-Building

Setting the Tone for Students

Smoothly transition from online to in-person/HyFlex classrooms by circulating expectations prior to class

You might consider preparing both in-person and HyFlex students for what class sessions will look like and what technology you're using (if any). You can also encourage HyFlex students to find a quiet space in which to participate where they won’t be interrupted and where background noise and/or images won’t distract other people if they are asked to contribute.

Define learning objectives and participation

Communicating learning objectives to students helps to keep them focused on what they are learning, and will help you and your instructional team determine what is most important to highlight in class. Use your objectives to consider what should or can only be done when your class is meeting and what might be movable to out-of-class videos, homework, or activities. Similarly, defining what participation looks like will help your students make progress towards these learning objectives, and allow for you to give feedback on engagement.

Clarify classroom expectations and roles through community agreements

Consider having a discussion with students about how to re-integrate classroom norms into the face-to-face and/or HyFlex classroom. By building these community agreements collaboratively with your students, you and your students will be more invested in the embodied classroom as a shared space. Topics to address include protocols for interacting and engaging during classroom activities with both in-person and HyFlex classmates, guidelines around mask-wearing, eating, and drinking in the classroom, and ways to seek help with any challenges that may arise in returning back to in-person learning.

Start small, collect feedback, and reflect

Going from teaching in person, to teaching online, back to teaching in person / HyFlex is likely a new experience for you and your students, and will certainly not be without its challenges. Reflect on which practices you want to transfer from online teaching back to in-person teaching, and which you want to leave behind. Encourage your students to provide feedback on their experience to help you reflect, revise, and try again next class.

Consider creating opportunities for students to interact informally

According to focus groups the CEP ran with Institutional Research in Fall 2020 and Spring 2021, the lack of social interaction in online learning spaces proved particularly challenging and demoralizing for students. In light of the transition back to in-person learning, consider creating opportunities for students to interact informally. This can be done quickly through icebreakers or activities that students can do as they enter the classroom right before class or as class begins. These bits of small talk or fun can go a long way in helping build community, and can benefit both in-person and HyFlex students in increasing students' comfort levels during this time of social, emotional, and academic transition.

Share campus resources

Some students may feel vulnerable and/or stressed given the continued and evolving impacts of COVID-19, both locally and internationally. Be mindful that an event of this magnitude that impacts the entire campus can have a substantial impact on students and their capacity to engage in coursework. Instructors may need to adjust academic assignments and examinations accordingly. If students express concerns or request accommodations, we advise that you refer them to campus resources like the Deans Office, Furman Counseling Center, Primary Care Health Services, or the CARDS office.

Suggestions for Community-Building

Fostering student engagement and building a sense of community within the classroom are processes that go hand in hand. Engagement involves much more than simply being present in class; meaningful engagement occurs when students are focused, interested, and motivated. Students tend to learn best when they are not only invested in the course content and the learning process, but also feel connected to others in the class (peers, instructors, and TAs). The interpersonal and social aspects of pedagogy can feel particularly tricky to facilitate when transitioning back to in-person and HyFlex classes. How can instructors facilitate meaningful community building? This section offers suggestions on how to build and foster community in the classroom.

Since meaningful interpersonal relationships can be strong motivators for students, the following offers suggestions to enhance instructor-student interactions in your course. These practices will help you get to know your students, build rapport, and cultivate a feeling of connectedness between yourself and your students.

Making meaningful first impressions are especially important for cultivating community in the classroom. Welcoming students to the course and letting students get to know you (and their peers) can help students feel immediately at ease. Take time to think through your first interaction with your students, whether it is in the form of an email, a syllabus overview, a course orientation, Canvas announcement, or something else, as the first interaction can have a lasting impression on students. Find more information about creating a course orientation for online classes at our course orientation page.

Model the quality of engagement you’d like to see in your students. Build presence in the course and stay in contact with students in both in-person and online interactions. For example, being accessible and present during office hours and demonstrating that you've engaged with students' work prior to meeting with them are two ways to communicate to students that you care about their learning. Additionally, you do not need to respond to discussion posts and emails immediately or constantly; however, if your interactions with students are impersonal, rushed, and/or infrequent, then you may be less likely to see students making quality contributions to the course. Inform students of the general time frame in which you will respond to emails and discussion posts.

Sharing your background with your students and your own personal experiences and connections relevant to your course can help your students get to know you better and show that you are enthusiastic about the course. For example, you might share your own academic and/or professional background, related pursuits, personal interests, hobbies, etc.

Consider incorporating brief check-ins throughout the duration of the course to show students that you care about their learning process. Interactions with students that occur outside of class time demonstrate that you are present and active. Possible options: weekly announcement or reminders via email or Canvas, distributing physical exit tickets at the end of class on a regular basis to glean student feedback, posing questions in the discussion boards. While announcements are often used to remind students of upcoming deadlines or changes to the course, you can also utilize announcements to share a highlight from a class discussion, share an article or upcoming event related to the course, or additional resources.

Reaching out to students, whether individually or in group settings, can positively impact student motivation and engagement. Expressing concern about the barriers students might be facing and offering compassionate guidance and support can motivate students to re-engage with the course. Sometimes, just feeling noticed is enough to motivate a student to re-engage—most students want to feel seen by their instructors and their peers. Options include: Scheduled first week and midterm check-ins, dedicated time for check-ins during class sessions, individual office hours.

For larger classes, consider using a questionnaire to check in with students halfway through the semester in order to get a sense of how they are feeling, their level of engagement in the course, and whether they need additional support. If your class is supported by TAs, they may be able to offer check-ins with students in their discussion sections as well.

Student feedback from Spring 2020 expressed that students appreciated instructors who set aside specific time during class (the first or last 10 minutes of class, a 10 minute break during class) for check-ins and casual conversations. Students can talk about how they are feeling and how they are doing. This dedicated time signals to students that their instructors truly care about their well-being both within and beyond the classroom.

Fostering Learning Communities

Why are student-student interactions important?

Within a learning community, students are collaborators who actively enhance and support each other’s learning. In order to foster a learning community in your online course, it is vital to pay particular attention to building student-student interactions that encourage trust, intentionality, communication, and collaboration. The following are suggestions for strengthening student-student interactions in your course.

In the early weeks of your course, it is important to establish a feeling of rapport amongst students. Ask students to post a self-introduction message to an online forum, respond to their peers’ postings, or another activity of your choice. Communicate what these introductory activities should look like—be specific and prompt students to get to know each other in ways that go beyond surface-level introductions. For example, instead of asking students to post 1-2 sentences to introduce themselves, you might provide more detailed prompts, such as asking students to share what they hope to learn in the course or a particular reading they are looking forward to.

Assign each student to long-term groups for the entire duration of the course. Dividing students into recurring small groups can help facilitate consistent interaction between students. These groups can be used for breakout discussions, group projects, or other collaborative work. We recommend groups of 5-7 (depending on course size).

Send students to breakout rooms on Zoom for 5 minutes at the beginning or end of each class to chat about anything. This can be a way to ease students into or conclude the class session and offers students an opportunity to interact casually with each other.

Facilitating Feedback from Students

Overview

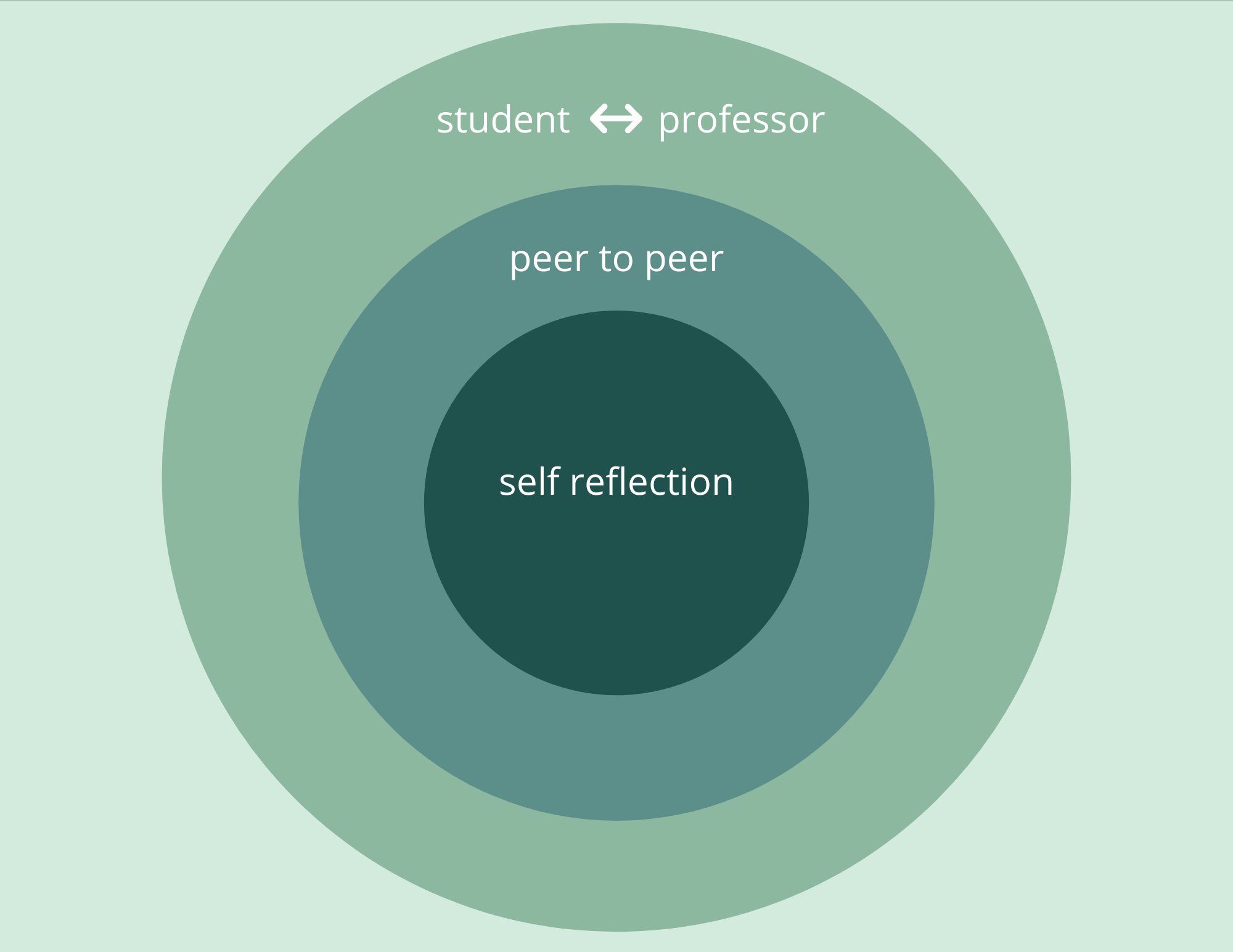

In the classroom, feedback is an important tool for reflection and progression. Useful feedback allows room for self-awareness, aligns students with learning objectives, and offers actionable ideas for improvement. Feedback in the classroom happens at four tiers: self reflection, peer to peer, student to professor, and professor to student. This section primarily addresses strategies for soliciting feedback from students.

Collecting feedback from students can help you determine if your teaching methods are effective and help make sure your students feel comfortable, empowered, and motivated. One key method to ensure these factors are present in your classroom is to consistently solicit feedback from students throughout the semester. Listening to students' suggestions and incorporating their feedback will not only make you a better professor; it will also increase students' ability to learn effectively from you. Outlined below are tips for procuring feedback from students, as well as tips for creating a classroom environment in which students feel comfortable enough to provide you with feedback in the first place.

Power dynamics exist in the classroom, grounded by our classroom roles and individual identities. Professors should remain receptive to student feedback and be aware of an unconscious tendency to selectively listen—and thereby devalue some students' experiences. While inviting students to speak with you during office hours is certainly a step toward a more inclusive environment, statements like "my doors are always open" do not sufficiently break down classroom barriers. Be sure to reach out to individual students you feel may be struggling, and take active steps to make them feel more comfortable. You could even ask students to anonymously share what would help them feel comfortable giving you honest feedback, via a Google Form or similar online tool.

Normalize naming your mistakes out loud and swiftly trying again (i.e. “Oops, I interrupted before you were done sharing that last idea. Could you tell us more about it?”). If there are habits you’re trying to eliminate in your teaching this semester, be transparent about them with your students. You could even ask them to gently keep you on track during class (i.e. "Our class agreed that we will direct full attention to whoever is speaking during our reading reflection discussions—if I'm beginning to flip through my book looking for a quote, that's a sign that I'm already thinking about my next point instead of listening to the speaker. In that case, I'd appreciate being quietly told, "Hey, ___ is still speaking").

Exit tickets are short Google forms with open ended questions for student reflection. The questions can be specific (i.e. “What questions do you still have about geothermal reactions?”) or broad (i.e. “At what moment in class this week did you feel most engaged with what was happening?”). Exit tickets should be disseminated on a regular basis to students, such as once per week. It can be useful to summarize exit ticket results to students after you have had a chance to read them. This will help you to understand any common areas of confusion, and allow you to identify topics or skills that students need additional support with.

Often, professors receive informal feedback throughout the semester and get too busy to act upon the ideas students have proposed. Research shows that in order for students to contribute their honest opinions to a classroom’s feedback culture, they need to see swift responses and a willingness to make changes. At the beginning of the semester, outline clearly what time frames students can expect their feedback will be considered, responded to, and potentially incorporated by the professor and/or TA(s). If you have received feedback that you are unsure how to implement, you can consult the Center for Engaged Pedagogy at pedagogy@barnard.edu.

Beyond soliciting feedback, one step toward incorporating feedback is to summarize to students their comments on your teaching methods. Be transparent about what the entire class thinks about the effectiveness of certain activities, as well as the fact that there are always areas for you to improve as a professor. These steps will assure students that you value their feedback, as well as model the growth mindset you’d ideally like to see in students’ own approach to academic work throughout the semester. These instances of sharing could take the form of summarizing results of exit tickets that focus on specific teaching methods. Let your students know the results of the tickets, and then state the action you will take to reflect those results in the classroom (i.e. “I read through the comments on your exit tickets. Half of you would prefer more time spent on lecture, and half of you would prefer more time spent on group activities. Because of this, we will continue both processes.” Or, “It became clear from your comments that the breakout rooms are not helpful. Therefore, we will be spending more time on group discussions instead.”).

Fostering Active Listening in the Classroom

The classroom is a highly communicative environment, meaning it is as important to facilitate listening as it is to facilitate spoken conversation. Active listening is the practice of focusing completely on a speaker, taking clarifying measures to understand their message, comprehending the information they have shared, and responding thoughtfully. Communication exchanges are a collaboration between all involved parties, regardless of who is speaking at any given moment. Therefore, fostering an environment that emphasizes active listening is key to engaging students in interpersonal communication, self-disclosure, and classroom collaboration.

As an instructor, you cannot realistically control all communication dynamics in the classroom. We all have un/conscious biases that can affect how we listen, how we demonstrate our listening, and to whom we choose to listen. While you have control over your own decisions in the classroom, you cannot control how others in the space react to them. Therefore, it can be helpful to think of your classroom as a garden and yourself as a gardener. While you cannot control how the plants grow and interact with each other, you can provide conditions to foster optimal growth in the space; similarly, your listening facilitation can encourage students to better support one another. Recognizing, questioning, and confronting your biases will also make you more adept at listening to a broad range of people.

Many of the listening techniques on this page come from crisis response training, which focuses on high stakes situations. However, these tools also make everyday communication much more effective. These are strategies that you can use to strengthen your listening skills in a variety of settings, and they work particularly well when used together. We’ll touch on more strategies later that are specifically geared toward fostering an active listening environment.

When you paraphrase, you present the speaker with what you heard, and give them an opportunity to clarify that you are on the same page. Paraphrasing is not verbatim repetition, but rather a statement that echoes key descriptive words/phrases the speaker used meshed within your own words.

Tentifiers are tentative, responsive statements that demonstrate active listening and strive to confirm what the speaker is expressing. Examples of tentifiers include, "It seems like... I wonder if... It sounds like... I’m hearing that...I hear you saying that... If I understand you right, you... Let me see if I’m with you so far; you… What I’m learning is…," etc. By allowing space for the speaker to correct us, these statements keep us from making inaccurate assumptions (which, according to cognition, is normal). Tentifiers help to align what students are expressing with what you think they are expressing, and give them the agency to confirm or deny your impression.

Validations are expressions of empathy; they let the speaker know that you've given thought to how their experiences may have led them to express certain opinions. By using validations, you can communicate to the speaker that what they're saying and feeling makes sense, and that you intend to make space for both of your views throughout the conversation. Examples of validations include, "It’s understandable that …. I hear that… I can imagine that … It’s totally fair that … It must be really challenging to... It makes sense that you think/feel.... I’m curious about … I care that you… I value that you…," etc. These statements allow you to empathize with the speaker without necessarily agreeing with their point. Additionally, it's important to remember that validations are not statements that start with, “I understand” or “I know.” These statements undermine the expertise a speaker has about their own life and experiences. Even when we practice active listening, we have no way to "know" someone else's perspective; all we can do is reflect on the parts of it that they have chosen to share with us.

Asking questions expresses curiosity in the speaker’s message, encouraging them to continue sharing. Questions are open-ended if they prompt sentences, lists or stories, or otherwise cannot be answered in one word. They often involve a who, what, where, when, why, and how.

- Clarifying questions invite the speaker to define terms the listener did not understand

- Examples: “Can you say that last part again?” “I’m having a hard time understanding your metaphor–could you tell me again in other words?” “Can you give me an example of___?”

- Probing questions invite the speaker to elaborate more deeply on their story

- Examples: “What was ___ like for you?” “What led up to ___?” “What’s on your mind now, after ___?” “Could you tell me more about ___?” “What is important to you that we take away from your story?”

Amplifying acknowledges the ideas and participation of speakers in the space. It helps us offer recognition to speakers—especially in a setting where multiple people are in discussion with one another—and listen while remaining aware of our own biases.

You don’t need to be in a position of authority to amplify within a conversation: consider role-modeling or directly encouraging students to extend this courtesy to one another.

Amplifying could look like:

- If someone lays out more than one point, and you just want to focus on one/reroute the conversation from what the person’s intention was, acknowledging that verbally (“I hear a lot of useful information in Ella’s comment– I’m first going to respond to [describe one point Ella made] and then return to [describe another point Ella made], if that’s okay.”)

- Providing callbacks in situations of interruption, which gives the interrupted speaker an opening to jump back into the conversation (“Thank you for that clarification, Riley. I know we jumped ahead but I want to acknowledge the comment Mel started making earlier; is there anything you’d like to add or emphasize, Mel?”)

There are two main types of interruption, each of which serves a different purpose and has different effects. One is meant for switching speaking turns in a conversation (cutting in to say something else), while the other serves as an interjection of enthusiasm and participation (saying “Yes!”, “I feel that," clapping, etc). While interruptions are often vilified in classroom dialogue, they are not universally harmful. Many cultural communication norms encourage interruption as a form of communal participation in a conversation. Additionally, power differences in a space between students and educators will also dictate how interruptions are received: while students may not be able to interrupt educators without it coming across as rude, educators often feel they can interrupt students whenever they wish because of their position of relative power. It’s most useful to observe when you’re interrupting, why you’re interrupting, and who you’re interrupting, and reflect on how the person you’re engaging with responds to being interrupted. Encourage your students to do the same!

Course orientation information adapted from Robinson et al. 1996 cited in Scagnoli 2001; Scagnoli 2001. Suggestions for community-building are adapted from University of Waterloo’s Fostering Engagement: Facilitating Online Courses in Higher Education Self-paced modules; Indiana University’s Teaching Online Self-paced modules; Chakraborty and Nafukho, 2015; Scott, 2003; Roddy et al., 2017.