Student Power and Privilege

Student Power and Privilege

Overview

It is common knowledge that student learning experiences and relationships are shaped by the different levels of power and privilege they hold relative to their instructors and the institution at large. Just as influential, although not as often recognized, are the power inequities that exist between students, which are often marked in terms of race, ability, and socioeconomic standing. It is necessary for instructors to recognize these dynamics of power and privilege and integrate pedagogical practices that address inequality and transform the classroom into a “brave space”: a space where students are encouraged to disagree respectfully, push the boundaries of their comfort zones, and not shy from emotional honesty in challenging conversations (Martinez 100). Outlined below are a few steps that educators can pursue to address issues of power and privilege between students.

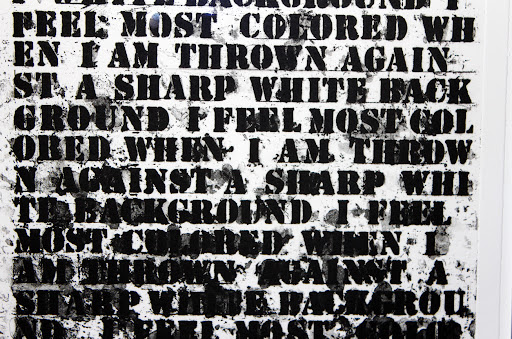

In this detail from Glenn Ligon's Untitled (1990), Zora Neale Hurston's statement, "I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background," appears as a repeating series whose accumulated paint eventually blackens the bottom half of the canvas, blotting out both the statement and the background against which it becomes legible. This work encourages reflection on race, not simply as a social category forged through discursive practices, but also as an affect—a bodily sensation—formed within and against an environment of whiteness. As this subsection suggests, this environment includes classrooms and the ways students interact with and relate to each other.

Practices

Inside the classroom, instructors must remember that their position of authority requires them to set the tone of the class. Particularly when navigating conversations about power and oppression, faculty members must be diligent and cognizant about the range of identities, both more and less visible, that make up their classrooms, and how students, especially marginalized students, are affected by their peers’ comments. This requires instructors to pay close attention to all parts of the conversation (including listening for microaggressions) to know when to intervene in response to comments or attitudes that harm the learning opportunities of marginalized students. Depending on the nature of a comment, an intervention might consist of calling-out a student’s harmful language, immediately and explicitly explaining how and why their words or practices were harmful, and observing that such comments have no place in the class. Or, an intervention might consist of calling-in a student’s harmful practices, encouraging them to reflect on what beliefs or viewpoints inform them, and providing an opportunity for the student to transform those practices by connecting them with what the class is learning. In any case, educators must make it clear that not every argumentative position that students might adopt is valid: for example, no classroom should tolerate or validate white supremacist statements.

As a preemptive measure, before starting a discussion centering around race and other identity-based issues, instructors might provide guidelines for the discussion or collaborate with their students to define community agreements. For example, guidelines might include encouraging the use of “I” statements to avoid invalidating or speaking for others’ experiences. On a broader level, instructors should consider adopting a multipartial form of facilitation, which can help account for the way power is distributed in groups and serve as a pre-emptive measure against microaggressive comments and attitudes. A multipartial method of facilitation requires the instructor to actively acknowledge and address a power dynamic within the classroom by supporting underrepresented voices, calling attention to the influence of dominant narratives, and fostering mutual responsibility for questioning those narratives. This is uniquely important since neutral forms of facilitation work to sustain existing inequities between students.

Such interventions from instructors are necessary because they set the tone and precedent for what type of space the classroom will be and what is (not) tolerated for the rest of the class. When instructors do not intervene in these moments, marginalized students are put in a position where they must carry the burden of speaking up against the very people that are doing harm to them. This dynamic, beyond its awkwardness, positions the student in a less-than-favorable environment in which to learn and thrive

Giving students agency over the materials covered in the classroom can help to neutralize power imbalances between students. An example of this might include reserving a section of the syllabus for students to identify materials and approaches that they believe will help them engage in a meaningful way with the class subject. Another might be to set up an activity at the start of the semester where students identify learning goals and name how exactly they will achieve them. Furthermore, instructors might use pre-class surveys or devote portions of class time to collaboratively craft community guidelines for discussions and small group work. Ultimately, the practice of giving space for students to exercise their agency in relation to class material can allow learning to become a reciprocal process that allows the classroom to become more collaborative in nature and facilitates a model of learning that actively engages with current events and issues personal to their lives.

Lastly, educators should adopt practices that allow students with very different personal and financial backgrounds to succeed in their classes. A good practice, especially in first-year courses, may be to introduce the entire class to the availability of resources such as Access Barnard (and others). This practice would allow students to access the resources and support systems they need without having to disclose their identities and circumstances to the instructor. Furthermore, instructors can develop pre-semester surveys that give students an opportunity to share information about themselves and their backgrounds that they believe will help them succeed in the classroom.

Reflective Questions

For faculty

What is my style of facilitating class discussions and how might this style contribute to power/privilege imbalances between students? Or, how might this style of facilitation challenge those imbalances?

For students

What aspects of my identity and experiences provide me with privilege and how does this privilege affect how I engage in academic discussions with my peers? How does it shape what I see as true and neutral?