Course Design

Course Design

Preparation & Planning

Adapted from the Center for Teaching and Learning at Columbia University, Georgetown University, the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning at Harvard University, and Swarthmore College.

Consider what can be realistically accomplished in the course. Can you keep everything on your original syllabus? Which activities can be most easily adapted online? Is it possible to prioritize certain activities or assignments over others? Keep in mind that the transition to remote learning may have an impact on which activities/assignments are most appropriate for your course.

It is more difficult to ad lib a class session while teaching remotely. Prepare sessions beforehand to ensure logical flow, clear instructions, and accurate placement of content. Class will be much smoother with organization beforehand.

Whether through Canvas/Courseworks or email, ensure students all have access to and are aware of this communication method.

Have a backup plan in case of technical difficulties. Consider moving classroom discussion to a written discussion thread on Courseworks.

Consider making anything you intend to present to students available; it can be helpful for students to have access to course materials independently (power points, audio, video, web sites etc.).

Think about how your methods for providing student feedback and grades could be moved to a digital space like email or Canvas (if they are not already digital). Consider office hours virtually through Zoom according to a schedule, by appointment, or both.

It’s important to consider how much work is reasonable to expect of students while at the same time ensuring that you’re covering the necessary content.

Consider which types of activities are appropriate and how you might offer different types of assignments to make the course more interesting and engaging for the students. Don’t try too many types of activities in one session, in order to minimize the chance of technical problems and confusion.

Making changes can have unintended consequences such as inconsistent information. This can create confusion for the students and it may be more difficult for you to recognize their confusion online. It may also take more time for you to explain things.

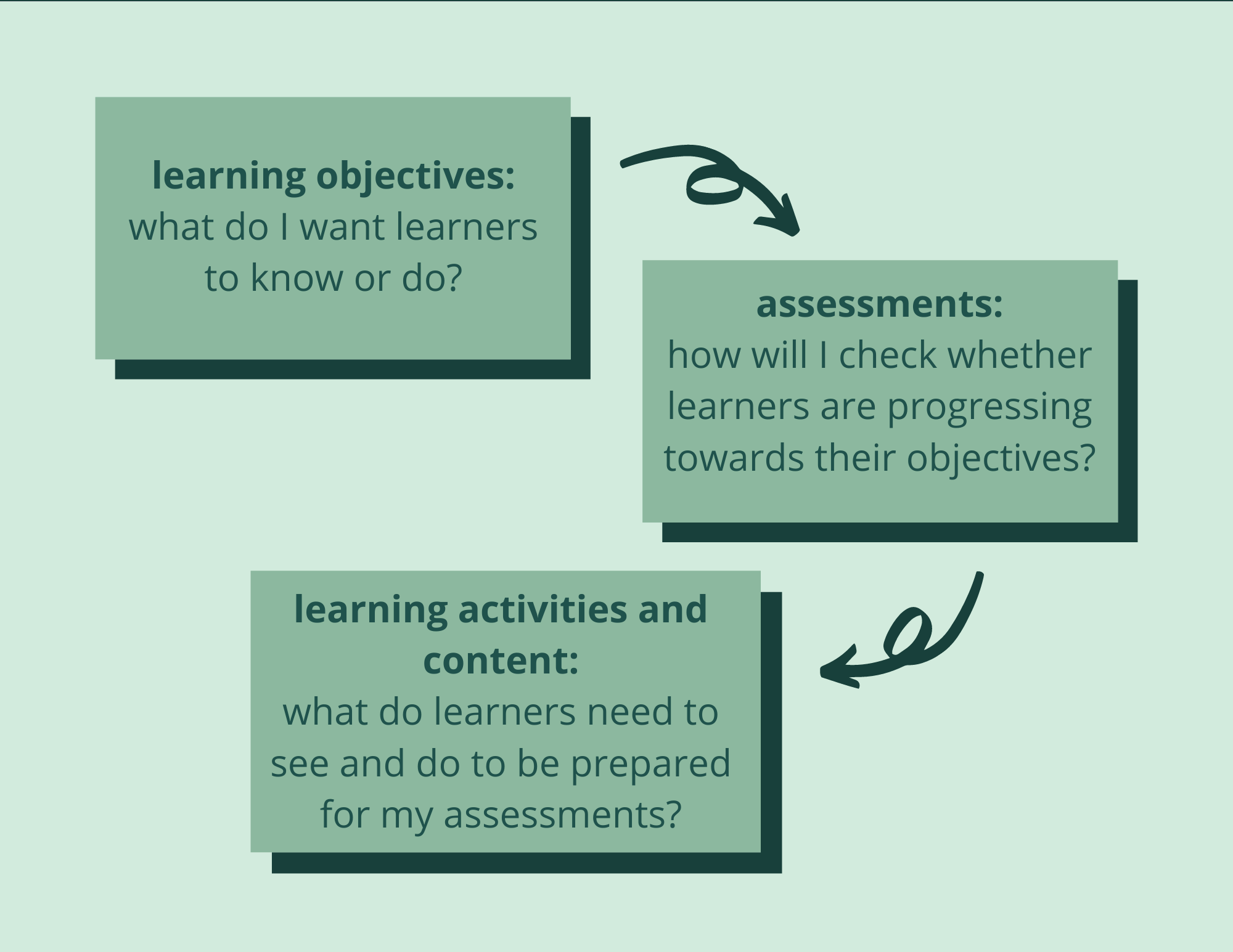

Backward Design

What is backward design?

Backward design is a framework for course design containing three parts: objectives, assessments, and learning activities. It’s known as “backward” because the instructor begins by envisioning the outcomes they want their learners to walk away with, rather than the content they’ll work with along the way. This is important because it sets a clear foundation for your class’ purpose and ensures every part of the learning experience you provide plays an active role in achieving clear learning goals.

The three main components of a backward designed course are:

- Learning Objectives: statements that reflect what a student should know or be able to do after completing your course

- Assessments: benchmark activities that demonstrate a student’s progress towards the learning objectives (such as projects, exams, presentations, facilitated events, etc)

- Learning Activities: everything that prepares students for course assessments. This could consist of content (such as course readings) or activities (discussions, group work, reflective writing)

Backward Design: Planning a Syllabus

Particularly if you have not used backward design in previous iterations of your syllabi, open up a fresh document to begin the process– this may ease the temptation to cling onto previous assignments or readings. Even if you are a seasoned backward designer, you may find that your learning objectives for a course change for a given semester, which will impact what assessments and learning activities best serve those needs.

This will help center your vision for desired outcomes of the class, and make it clearer for you and your students how all assessments and learning activities build towards the course’s central objectives. Moreover, setting learning objectives first helps you account for situational factors in your teaching design. By starting with objectives, educators can adjust the scope of their course’s goals, which will be a big help in finding a reasonable amount of content and assessments to assign along the way.

To phrase these objectives, it is helpful to ground your phrases with powerful, measurable verbs that paint a clear picture of the actions you envision. Bloom’s Taxonomy, a model formed by cognitive psychologists and education researchers to describe the actions learners take when mastering concepts or skills, is a great framework to consider when searching for verbs that express those actions. Consider these verbs as a starting point.

The context in which you will be teaching the course is key information for establishing appropriate learning objectives. This context can be impacted by learning modalities, world events, who the students in your class are and what goals they have for themselves. Consider all of the above when deciding what content and skills are most important for this group at this time.

Based on how closely the content meets your learning objectives, categorize content as “must knows”, “need to knows”, and “nice to knows”. “Must knows” are imperative knowledge, prerequisite, and foundational ideas. “Need to knows” are less of a priority but likely to be important later (based on requirements of advanced courses in the discipline, curriculum standards, or requirements of professional practice). “Nice to knows” add depth or interest to a topic but can be deemphasized without compromising foundational knowledge. In compressed format courses, it is useful to prioritize “must knows” and “need to knows”, and engage with complex and important topics (“must knows”) early in the course.

It is crucial to recognize that this will likely be the first time both you and your students engage in a hybrid learning environment. To honor students’ agency in making this experience meaningful, plan not just for assessments of your students throughout the semester, but assessments of your course as well. Offer your students opportunities to provide you with feedback multiple times throughout the semester through an anonymous Google Form, email, or Zoom check-in during office hours.

Learning objectives serve as the tool for vetting all aspects of the course. Any assessment, assignment, or learning activity that doesn’t provide a specific answer to that question may need to be reconsidered or scrapped altogether. This is especially important for immersive courses, for which faculty must be even more selective with their content given schedule constraints.

Asynchronous Learning

Overview

Asynchronous course time enables faculty and students to engage with the course material and each other at different times, while still meeting the same learning objectives and course goals. Well-designed asynchronous and synchronous components of a course work together to address course learning objectives, accommodate various learning modalities, allow students to engage with course content in meaningful ways, and facilitate deeper learning. Integrating asynchronous components also accommodates students who are located in different time zones as well as students with varying levels of technical accessibility (e.g. hardware, software, and Internet). This section provides some best practices for asynchronous instruction and offers suggestions for facilitating meaningful asynchronous engagement.

Suggestions for Asynchronous Instruction

- Utilize asynchronous activities to prepare students for in-class activities, and vice versa. Asynchronous interactions can reinforce or extend those that occur in the classroom, and vice versa. For example, students can provide feedback to each other outside of class and then respond to the feedback in synchronous sessions. Or, students can finish a discussion that started in class via asynchronous discussion boards. Feedback can come in the form of responses, questions, provocations, or evidence and the modes can vary from audio recordings or texts to images or clips. In addition to assigning readings, you can provide some course content online through video tutorials or documentaries or require students to take an online quiz before attending class.

- Let asynchronous student work inform your lecture.

For example, have students post key definitions online for the whole class to edit and refine. Before class, review these and pick one or two that deserve discussion; you can also address learning issues or best practices by asking students to share what they are confused about or struggling with and using this feedback to support your teaching, pace of the course, and content.

- Make an effort to bring in asynchronous student voices.

Incorporate or reference topics and points brought up in asynchronous discussions to include the voices of students who are participating asynchronously in synchronous class discussion or lectures

- Collaborative reading/annotation asynchronously.

Students can read a wide range of texts (websites, course readings, news articles, and primary sources) and comment and annotate the texts, engage with one another via their comments to create a written dialogue and reflection about course material. Contact courseworks@barnard.edu to integrate Hypothesis.is or Persuall, two social annotating platforms into your Canvas course. Contact pedagogy@barnard.edu to access a workshop on both digital platforms during the CEP’s Summer Pedagogy Symposium to decide which one is right for your course.

- Foster rigorous asynchronous discussions using online discussion boards.

Meaningful asynchronous discussions can be generated through the active facilitation of online discussion boards. This is particularly important for the learning experience of students who cannot join the class for synchronous discussions. Regular usage of asynchronous discussion boards fosters consistent instructor-student and student-student interaction, which can help enhance student engagement throughout the duration of the course.Taking advantage of asynchronous discussion can also be useful if you would like to allot more class time to other activities that are not discussion based. Encourage students to contribute to asynchronous discussion by making participation in discussion boards part of the course requirements.

Before the course begins: set clear student expectations with deadlines, discussion requirements, and grading procedures. Creating discussion board rubrics is helpful to demonstrate to students what you value in discussion board responses and to emphasize the importance of this type of participation for the course. Set boundaries by determining and sharing what days and times will you be on the discussion board so that you don’t feel like you have to post or respond 24/7.

During the course: Try to respond to more than one student at a time, connect comments or choose a thread in which you could address multiple students and address students by name when responding. The more you respond the more eager students will be to engage. To maintain meaningful engagement, your responses can maintain focused conversations, bring threads back to the main topic, ask for clarification, synthesize and add additional content knowledge, recommend additional resources and balance group dynamics.

- Use the online discussion board as a presentation space.

Meaningful asynchronous participation can occur through innovative uses of discussion boards beyond conventional reading responses. Presentation skills can be fostered asynchronously by using the discussion board as a presentation space. For example, students might record a simple video of themselves presenting on an assigned topic. Or, they can post a link to a voiced-over visual presentation such as a slide deck or a selection of images. Presentations can also take the form of creating and posting a graph or other visual, and then a video or audio recording of themselves explaining it. Having students review and analyze their own video recordings can also be an effective way to foster reflection. There can also be requirements for other students to view, respond, and ask questions of the presenter. For example, the presenting student will post their presentation on the weekend, the class will view the posted presentation during the first half of the week, and post a comment or question by Wednesday. The presenter student would then return later in the week to respond to comments and questions

- Utilize the online discussion board as a gallery and/or reflection space.

Using the discussion board as a gallery for meaningful visuals (as opposed to only text-based discussion) can help heighten engagement in an asynchronous learning space. Asking students to engage with images can encourage them to think more creatively about course topics. For example, prompt students to post a photograph or other media relating to a topic and then reflect on its connection to course material.

- Create a workshopping space using a digital platform.

An online discussion board can be set up as a space for collaborative work. Using this space as a work space helps students engage in meaningful action involving their topic—for example, group problem solving—and provides a record of work that can then be drawn upon in future assignments or class discussions. This can also be created using collaborative Google Docs, Wordpress Blogs, or another shareable platform. Suggestions include: workshopping research questions or excerpts of writing, solving a problem collectively, responding to an assigned question or summarizing a reading collaboratively. See the Digital Tool page for additional suggestions.

- Balance asynchronous and synchronous instructional elements

While adapting your courses for online learning it’s important to remember that when you add additional components to your course you do NOT create additional homework for students. If you provide recorded lectures for students to view outside of class time or require discussion board posts to extend the in class discussion to out of class time ensure you are monitoring the readings and individual assignments that you are simultaneously requiring for the course.

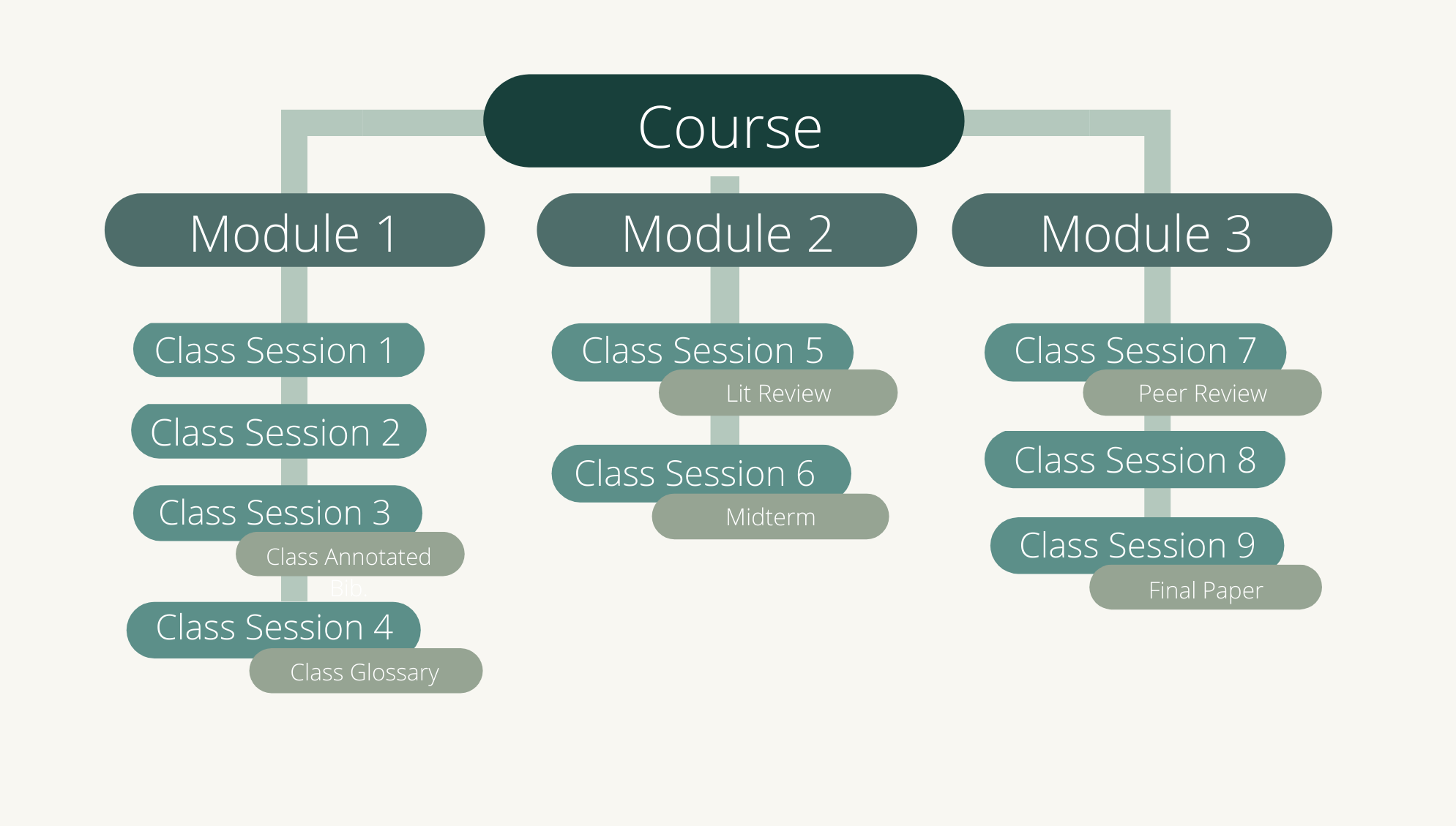

Canvas Modules

Overview

Modules are a way to organize your course by grouping information and activities. Modules are organized homogeneous collections consisting of resources and assessments that focus on a discrete topic, subject, or theme. A course organized by discrete but connected modules can be changed and adapted more easily than a course structured with a single arc.

At the lowest level, modules organize. Modules focus on a single discrete topic, subject, or theme; they contain all content (e.g., readings), assignments, and assessment thereon. At the highest level, modules work toward the achievement of course objectives. Each module can be a self-contained unit with its own sub-learning objectives, assessments, content and resources that link up with the course’s main learning objectives. The modules are like train cars—when linked together they structure your course and support the learning cycle. Your course modules can be organized by: topic (e.g. Classical film, Modern film…); time (e.g. Week 1, Week 2…); activity (e.g. Final project…); or any combination of these.

Benefits for Online Learning

- Paces the learning experiences to sequence information and activities and keep students from feeling overwhelmed with too much information

- Enables students to monitor and reflect on their learning experiences

- Discourages cramming by providing clear benchmarks and points of engagement

- Sets up a visual overview for clarity (table of contents)

- Provides organization to scaffold learning

Module Design Considerations

Module Objectives

Use strategies described in Backward Design to conceptualize a rough set of module objectives that connect back to your larger course objectives. Ask yourself, what do you want students to achieve in this unit?

Introduction

Every module must Include an “introduction” page to the module that details the module. Ideally, it includes a list of required readings, discussions, assignments, and all expectations (e.g., outcomes/goals, student conduct, grading standards, rubrics, completion date(s), etc.).

Tip: Be explicit.

Organization

Consider the order in which content is organized in modules and how learners will interact with it. Reduce cognitive load by keeping module structure simple and uniform throughout the course. Use indentation to reinforce intra-module flow. A module includes all content (e.g., pages, files, links, etc.) and activities (e.g., discussions, quizzes, assignments, etc.) for a single topic, theme, or subject.

Tip:If a module is too large, consider breaking it up into smaller modules.

Explanation

Modules cover a single topic or theme thoroughly. In a single module, links to all files and assessments provide an overview of the topic before learners engage the material.

Tip: Consider an overview module for the entire course to set the stage. Use that space to introduce the course, yourself, the syllabus, and more. If rubrics and policies are the same throughout the course, consider creating a module specifically for them, and refer to it often.

Naming Conventions

Modules should be named clearly and consistently throughout the course. Consider adopting a format that includes a module name, topic/theme, and number.

Tip: Avoid dates in module names.

Examples:

“Welcome to [Course Name]”

“Course policies and grading schemes”

“Module 1 - On becoming attached: Bowlby’s attachment theory”

“Module 2 - Attachment styles beyond Bowlby and developmental theory”

(since module 1 and 2 are small, they are paired together in a single week)

“Module 3 - Understanding intelligences”

(module 3 will take a week.)

Control

Canvas can control the availability of modules at an individual student level. While this is a very optional, advanced use of modules, it ensures learners progress through your material based on requisites and requirements.

Prerequisite modules: Ensure students complete required prerequisite modules before progressing to a module. Link to Canvas Resource

Required materials: Ensure students complete required readings and activities before marking a module as complete. Link to Canvas Resource

Immersive Format Courses

Immersive format courses may present unique challenges in terms of pacing and content, as they are only 7-weeks long but meet for longer periods of time each class session. This section offers strategies for designing immersive format courses and enhancing student engagement within them.

For compressed format courses, focusing on depth over breadth of learning enhances the overall experience of immersive courses. Delve into fewer areas in more detail and concentrate on major concepts rather than cover large amounts of information. Because immersive format courses take place over just 7 weeks, it is preferable to design for depth over breadth so that students will be less overwhelmed with content and more capable of retaining knowledge. Prioritize learning resources and activities that encourage deeper engagement and higher-order learning—synthesizing, analyzing and problem solving—over content acquisition.

Review teaching and study materials, including course readings in order to determine what aspects of your course are “must know, need to know, and nice to know.”“Must knows” are imperative knowledge, prerequisite, and foundational ideas. “Need to knows” are less urgent but likely to be important later, especially for advanced courses or further study. Nice to knows” add depth or interest to a topic but can be deprioritized without compromising baseline knowledge. Prioritize “must knows” and “need to knows” and engage them early on in the course.

Consistency, structure, and organization are key aspects of a successful immersive format course. Well-organized courses positively impact student motivation, focus, and engagement. Without organization and clear presentation of material in an easy-to-follow format, immersive format courses may become overwhelming and confusing. It is helpful to align course content, learning activities and assessment tasks, and make these connections clear to your students. Internal consistency between learning activities, assignments, assessments, and course content enhances student engagement. While organization and structure are important to maintain, keep in mind that things may not always go according to plan and it’s also equally important to be flexible!

Since immersive format courses are longer than traditional lectures and seminars, consider incorporating 5-10 minute water and/or stretch breaks throughout the class session.

Use mixed methods of delivery to vary pace and stimulate interest, including activity-oriented and discussion-focused instruction. If you need to lecture, consider dividing lectures into smaller chunks. At the end of each lecture block, have students engage in an activity that complements the lecture content. Students can demonstrate their understanding of the material just covered through check-in activities such as a quick quiz, a poll, a contribution to a Canvas discussion thread or Zoom Chat, or a short, written reflection. These activities help ensure that students are engaging with the content and help gauge student understanding and skills. See Online Lectures and List of Active Learning Activities for more.

Assign shared reading. For example, instead of assigning all students three texts to read prior to class, divide the class into three groups. Assign each group one of the three selected texts. In class, students summarize their assigned reading to those who have not read the same text. Implement pre-reading assignments that prime students for new content. Excerpt readings to help students focus on key components of a course.

Assign frequent, shorter assessments to accommodate the shortened time frame and potentially faster pace of an immersive format course. Ongoing assessments that incorporate a mixture of low and high-stakes tasks enhance student motivation and engagement and create opportunities for students to demonstrate learning throughout the course. Shorter, more frequent assessments also provide students with consistent feedback early on in the course.

Divide substantial assessments into shorter, more frequent tasks in lieu of or alongside substantive assessment. For example, you might choose to create weekly quizzes instead of conventional midterm and final exams that account for a significant percentage of the course grade. Or, use formative assessments in addition to a substantive final exam. Other options include implementing daily reviews, pre- or post-lecture short quizzes, and short writing assignments. Consider utilizing assessments that facilitate faster turnaround for feedback. Conventional assessments like exams and papers, may require more time to read and grade, whereas self-scored pre-and post-tests, class presentations, graded class participation or discussion facilitation, and oral exams provide opportunities for immediate feedback.

Consider scaffolding long essays and papers, group assignments, and research papers involving primary research that may be challenging for students to complete and instructors to provide feedback on within a compressed time frame. Suggestions include deconstructing a final paper into smaller parts to be completed throughout the course, assigning multiple students to write different parts of one paper in collaboration, and/or using class time to generate research questions as a class, develop a class bibliography, or workshop paper outlines. Alternatively, writing skills and research skills can still be taught without the completion of a full paper. Some possibilities might include assessing students based on quality of research and a well-written abstract with a clear argument, or assessing students’ outlines and annotated bibliography instead of full paper. You might also set aside time during class sessions for students to work on final projects. For example, this could take the form of structured individual writing time or devoting part of class time for peer workshopping students’ writing.

Create opportunities for reflection on material through the use of journals, small group breakout sessions, online discussion forums, and informal individual assignments that require feedback from the larger group. Gauge whether the pace of the course is appropriate by offering students an opportunity to provide feedback through brief surveys or in-class check-ins.

Suggestions for immersive format courses adapted from Freeman et al., 2018; Kops, 2014; Samspon et al., 2011; Scott, 2003. Asynchronous learning materials adapted from Cornell Center for Teaching Innovation Resources for Blended Courses; Purdue Repository for Online Teaching and Learning; Riggs and Linder, 2016; Swan et al., 2000. Module design considerations adapted from Riggs and Linder 2016.