Online Pedagogy Strategies

Online Pedagogy Strategies

Restructuring Online Lectures

Online Lectures Overview

Lectures are highly useful for relaying key concepts, but online lectures may lead to feelings of increased disengagement among students. This section offers strategies for enhancing active learning, student engagement, and focus in online lectures.

General Suggestions

- Plan with learning goals in mind

- Activate prior knowledge

- Capture attention and emphasize important points use effective multimedia

- Elaborate through examples

- Provide reflection opportunities

- Use retrieval practices

- Question for critical thinking

Shorten Lectures

Research shows that student engagement drops significantly after the first 15-20 minutes during uninterrupted lectures. Keeping in mind that students may feel additionally distracted in remote learning environments, consider breaking a lecture into small blocks with pauses or activities in between. Time suggestion for lectures: 12-15 minute lecture blocks, alternating with 5-15 minute activities.

Plan with Intention

Make sure the task and purposes for learning activities are clear to students. When planning your course, consider the connection between learning activities and learning objectives. Setting clear learning objectives prior to teaching the course can help you prioritize what material is essential to student learning and help determine what kind of content should be covered through learning activities as opposed to conventional lecturing.

Set Clear Expectations for Student Engagement

Students may come into a large lecture expecting to listen passively, especially in a remote learning context. Emphasize from the first day that your class will involve active learning and that you expect students to participate.

Punctuate Lectures with Learning Activities

One of the best ways to foster active learning in a lecture-based course is to integrate learning activities so that they build on the content covered in lectures. Consider pairing each portion of a lecture (10-15 mins) with a whole-class or small group learning activity that reinforces or further explores lecture material. Learn more about active learning activities you can include in your lecture.

Assign Student Roles

Give responsibilities to students to assist with full-class activities and small group tasks. Students can rotate through roles like: Zoom chat moderator, discussion facilitator, small group discussion note-taker, discussion board post summarizer, etc. Assigning roles to students not only helps the class run more smoothly, but also enhances student participation and active learning.

Use "Preview" Activities

Upload lecture slides ahead of class for students to preview material, if possible. Providing lecture slides ahead of class time allows students to prepare for your lecture and identify areas of focus before class. Other options include circulating a short article or video for students to view prior to class, to be discussed during class time. Time suggestion for lecture preview activities: 10-15 min

Use Pre- or Post-Class Assessments

Low-stakes pre- or post-class assessments can help you gauge student understanding and keep students motivated to engage with the lecture. Pre-class assessment idea: A short questionnaire at the start of a new unit or new topic that evaluates students' background knowledge. Post-class assessment idea: An "exit-ticket" at the end of a class session with reflection questions based on lecture content.

Flipped Lectures

Record short lectures for students to view asynchronously. Recorded lectures prepare students for synchronous class time, which will be used for collaborative work, discussions, problem- solving, and other active learning activities. Learn more about the flipped classroom.

Guest Lectures

Inviting a guest lecturer to speak in your class can help shake up the routine of class sessions and bring course content to life. It may also be encouraging for students to see and interact with a scholar whose work they have been studying. Guest lectures could also be substituted by alternatives like video clips or recordings of interviews

Tips for Zoom

A sample email* that can be edited to your preferences:

“Our class will meet online through the Zoom. We will adopt the same rules and norms as in a physical classroom (take notes; participate by asking and answering questions; wear classroom-ready clothing). For everyone’s benefit, join the course in a quiet place. Turn on your video. Mute your microphone unless you are speaking. You may want to test your microphone and web camera prior to class and make sure that your video background is appropriate. Consider closing browser tabs not required for the course to minimize distractions. This form of learning will be somewhat new to all of us, and success will depend on the same commitment we all bring to the physical classroom.”

*Adapted from Harvard University’s Best Practices for Online Pedagogy

Creating a class outline that signals to your instructional team and to your students what technology, tools, or platforms they will be expected to use as part of class is also a good practice. This helps signpost to students what is coming up, and transparency about technology use gives them an opportunity to prepare so that they are ready to engage once the activities begin.

If you have an instructional team (e.g. co-instructors or TAs), determine the roles that you will play during class. Two such roles include the instructor who leads the class (providing the main voice and being the person on camera throughout the learning experience) and the instructor who supports the lead instructor (helping to answer questions on chat, to set up any online tools (e.g., breakout rooms, polls), and to assist with troubleshooting if students have any problems).

If you use breakout rooms, the supporting instructor or TAs can also help facilitate small group discussion. Making these roles clear to students is helpful so that they can engage the appropriate person if they need help.

Students can set up their headsets, camera and microphones and to ensure that they are working properly.

Let students know who is allowed to and/or responsible for the shared content.

Consider requiring students to turn on video as part of their participation in the online course to encourage enhanced presence and engagement in the class. Students may also feel more attentive knowing they are visible on Zoom.

Remind students to be sure that their background is appropriate while sharing video, along with how their image is displayed to the rest of the class.

Explain how you want students to request an opportunity to speak. For example, raise hands or submit a question via chat box.

It may be more difficult to read students’ body language over Zoom and students may inadvertently speak at the same. Students less inclined to participate in class may also have more difficulty speaking in online discussions. Consider diligently pausing and asking if anyone else has more thoughts before jumping to the next topic.

Set ground rules for use of text chat. Discourage "side conversations" that will distract students from the ongoing conversation. Explain what is and isn't appropriate for them to post.

Schedule meetings with students that you would normally meet face-to-face with by using a Zoom meeting.

Open a Zoom session for student led discussion or instructor led review, and allow students to enter as necessary.

ATLIS's website has updated information on zoom tutorials and information on online learning.

Active Learning Activities

An active learning strategy is any task that encourages students (1) to do something with the concepts, tools, and ideas that make up the content of a course and (2) to reflect on that process of doing. Rather than suppose that students are simply recipients of knowledge that the teacher holds and shares, active learning emphasizes the processes of discovery, collaboration, application, and reflection. In an in-person or HyFlex classroom, these strategies can prove particularly helpful not only in keeping students engaged and feeling like part of a community, but also in providing instructors with important information about how students are learning.

General Suggestions

- Incorporate strategies that align with your learning objectives.

- Split students into small groups to encourage collaboration and build community.

- Allow for multiple forms of interaction with course material.

- Prepare simple, clear instructions for both in-person and HyFlex students.

- Determine whether activities can be completed in one class or stretched over several.

- Provide time and space for students to reflect on the activity.

- Develop feedback mechanisms that students can use to share what they learned.

Having students periodically collaborate in an application like Google Docs to brainstorm or take notes on a presentation can be an excellent way of increasing the accessibility of your class and encouraging students to critically reflect on how they are organizing and representing information. It also can be used as a community-building strategy in HyFlex formats.

In HyFlex formats, Zoom’s chat feature can be used in a number of ways to encourage students to engage differently with the course content and each other. For example, you may use the chat to have one group of students pose a question and another group answer it. Or, you may ask students to use the chat to share important, compelling, or confusing quotes that they want to discuss in more detail. Professors should still consider offering accessible text based communication methods within an in-person class to encourage various forms of participation, such as a Canvas discussion board, Slack channel, or email.

At the end of class, asking your students to fill out an “exit ticket” before they leave the classroom can be a way of gathering information about what your students have learned and what they are still trying to understand. For the instructor, the information collected in these tickets can help direct your course prep by helping you identify the topics your students are still trying to grasp (or alternatively, have apparently grasped quite well, thus allowing you to move forward with other parts of the class). It also gives students the opportunity to concretely identify the important takeaways and to name in detail the questions they are still facing. Google Forms and Canvas Quizzes provide an easy way to make and distribute Exit Tickets to both in-person and HyFlex students.

Give students keyword(s) and prompt them to jot down related terms for 2-3 mins. Then, ask students to share and explain their lists and to draw connections between lists or to revise and expand their own based on the conversation.

Develop a prompt that students can reasonably respond to in written form within a short span of time. For example, you may ask students to spend three minutes writing about the most important, surprising, or challenging thing they feel they learned in class that day. Or, you may ask students to use five minutes to identify a claim in a course text that they find intriguing and to meditate on how they might transport that claim to a new context. While this activity can be incorporated into class meetings, it also can be combined with a periodic journaling assignment that encourages students to track what and how they are learning over time (see below).

Give students a prompt, a series of statements, or other material that contains errors or misinterpretations of the material you have been covering in your class. Students then can work individually or in small groups to find and correct these errors. This strategy might be incorporated with a think-pair-share or small group activity (in which case, you may want to give your students time to present their findings to the class) or it might constitute an assignment of its own.

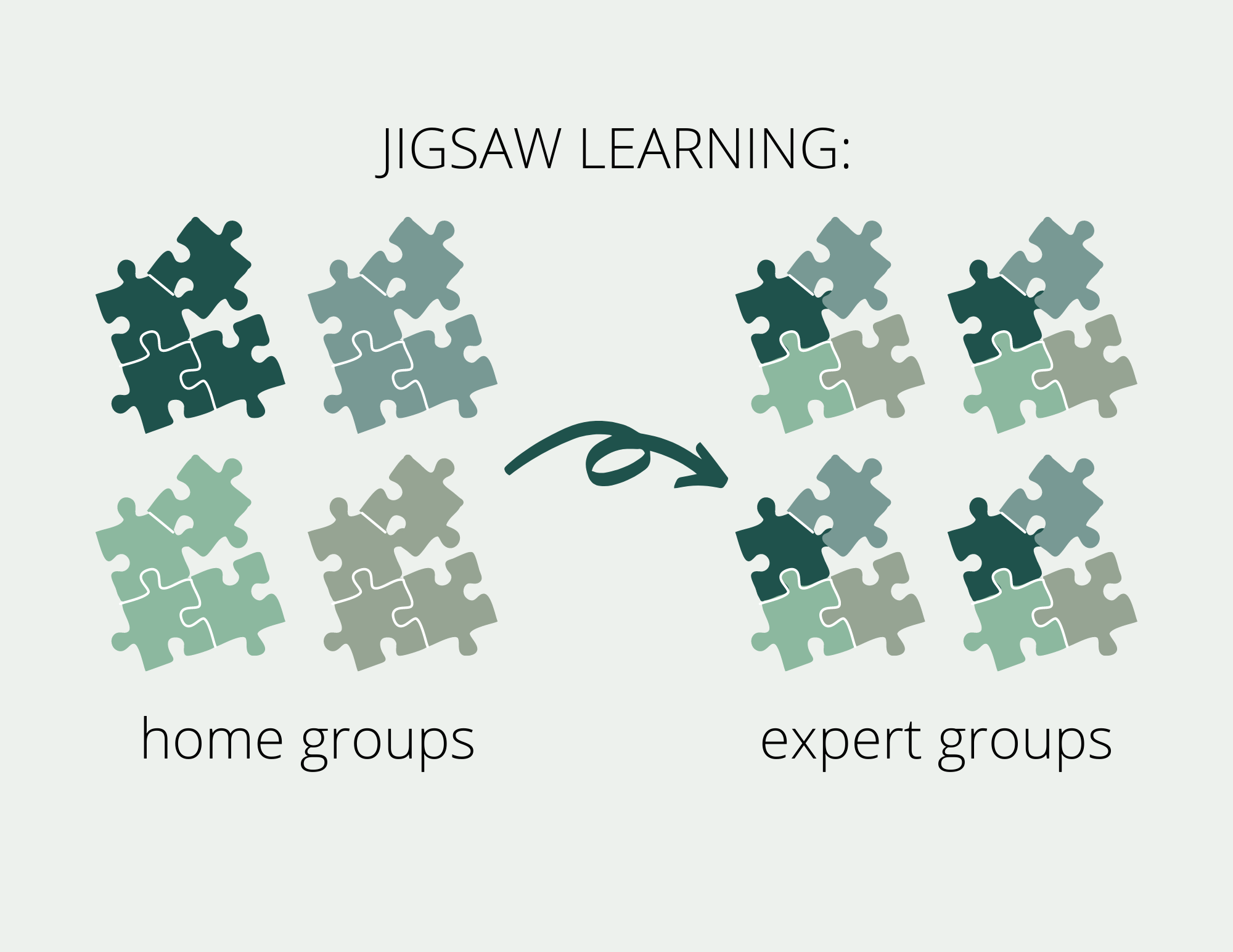

In a jigsaw discussion, students participate in two rounds of small group activities. Divide students into an even number of small groups, with one student appointed as a leader of their group. In the first round (“focus groups”), each group of students is given a different “piece” of a larger topic to study or discuss, with the task of producing notes or a brief presentation on what they have learned. All of the group members take time to study their own segment before being placed into a new round. In the second round (“task groups”), in which each new group has a representative from each of the first round groups, the students present to each other the work that they completed in the first round of discussion. Jigsaw discussions help show students the variety of ways that knowledge is constructed and can facilitate interaction between in-person and HyFlex students.

Inviting students to reflect on the course content or a particularly complex question over the course of an extended period of time can be an effective way of encouraging students to reflect not just on what but how they are learning. A consistent, low stakes journaling project that is periodically turned in for feedback or combined with think-pair-share activities allows students to develop and accumulate analytical skills at a pace the students set for themselves.

Ask students to write down one word that they feel they would have to use in order to explain what you are covering in class to someone who has not engaged with that topic. After they’ve written down their word, have them post that word to a board or other surface and invite them to look over the list as a group. (In a classroom, you may have students write these on post-it notes, but you can adapt this exercise for HyFlex classes by using an application like Jamboard.) Then, invite one student to explain why they wrote down the word that they did and to move that word to a new area of the surface. From that point, other students volunteer to place their word in relation to the first one (perhaps extending from it or developing a new branch), until a visual and textual representation of the topic in question has been produced.

Assign a small group of students to a panel-style discussion about a reading or course relevant topic that will take place on a particular day in class or by a particular time on a discussion board. Circulate a couple brief questions in advance to just these students and ask them to prepare their own answers and to be ready to engage in conversation with their co-panelists. Observers of the panel should listen carefully, take notes on what they feel made an effective answer in the panel, and answer the question themselves as the panel transitions into a broader discussion.

Polls are a quick, simple strategy that can be carried out in real time in order to get a sense of what your students are understanding or thinking about as they engage with the course content. From the student’s perspective, anonymous polls can also lower the pressure they may feel when asked a question or asked to provide an interpretation. Zoom allows you to set up polls in advance of meetings and deliver polls during class, which may be helpful in HyFlex formats. Google Forms is also a useful option for both in-person and HyFlex classes. Before developing poll questions, consider what kinds of information you want from your students, how you can best get that information, and how you will incorporate that information into the class.

Prompt students to find material that relates to the readings or discussions for a week and to reflect with each other on the connections between what they are learning and what they have found. For example, students might be put in groups, each of which is assigned to find and draw connections between course content and the following items: a news article; a podcast; a meme; a reading from another class; and a movie scene. Any items collected in this scavenger hunt might be reflected back to the students in a shareable document or section of the course site.

Whether you are teaching a seminar or a mid- to large-size lecture, putting students in small groups where they will work through a problem, consider a case study, do a close reading of a text, connect ideas to personal experiences, identify tensions in an argument, or any other number of activities, can be a valuable way of building community and introducing opportunities for students to apply the key practices and concepts of your course. In HyFlex formats, you can utilize Zoom’s breakout room feature in order to put students in small groups. Make sure you leave time for groups to share their findings with each other.

Provide the students with a jumbled list of items and ask them to put them in order. (In a classroom, you might do this with strips of paper, but in a HyFlex classroom you may use an application like Jamboard to carry out this exercise.) These items might be historical events or steps in a physical, environmental, or chemical process.

Students often report that some of the most valuable insights come from their peers. Short presentations can be an effective way of encouraging students to gather, produce, and communicate knowledge, and also gives the instructor an opportunity to assess how students are engaging with central concepts and arguments from the course. Students may be asked to guide discussion of a course text or may be invited to develop and deliver original research on a key topic. Tools like Google Slides and Screen Sharing can make both collaborations on presentations and the presentations themselves easy to include in class time, especially in HyFlex formats.

If your class incorporates a significant amount of discussion, a think-pair-share activity can be an effective way of giving students time to engage with a complex topic and can encourage participation from students who may feel that the pace of a class discussion moves faster than they would prefer. In this format, the instructor poses a question, problem, or scenario that the students engage with over the course of three steps: (1) thinking through what has been posed individually; (2) pairing with a colleague to discuss their ideas; and (3) sharing their key findings with the class as a whole. When incorporating this strategy into in-person class meetings, it is important to include time to explain the activity and leave students with adequate time to move through the steps. For HyFlex students, consider modifying this strategy for a discussion board (i.e., students may be assigned to small groups to share and respond to one another by a certain date).

Digital Tools

Overview

Digital tools can provide multiple ways of building community, practicing active learning, increasing accessibility, and assessing student progress in HyFlex classes. For up-to-date information on Ed Tech tools at Barnard, please visit the page on the Annotation, Discussion and Collaboration Tools webpage by Barnard ATLIS. Faculty are encouraged to reach out to ATLIS at courseworks@barnard.edu to discuss which tool is best for their needs.

Suggestions

- Incorporate tools that will advance your learning objectives.

- Do not overburden students or yourself with too many digital tools.

- Use digital tools in combination with active learning strategies.

- Test tools yourself or with colleagues before assigning them to students.

Assessment and Remote Learning

Overview

When adapting assessments for remote learning, instructors must consider several factors that impact assessment of student work and performance. In addition to considerations, this section also makes suggestions for overcoming some of the assessment challenges that occur when students are learning remotely.

General Considerations

- Context in which assessment occurs

- Purpose of assignments

- Transparency of assessments

- Academic Integrity

- Student accommodations and autonomy

- Metacognition and self-assessments

- Course Pace

Context in which assessment occurs

Equity in Assessment

While grading has always been a complex part of courses, approaching assessment equitably becomes even more challenging when students are learning remotely, especially during such a disruptive and difficult time. Issues such as access to technology (bandwidth, internet, hardware) makes taking exams or even engaging in the material and with the class very tough. Cheating becomes harder to prevent when students have access to different and immediate material. Using proctoring services may help with cheating but may cause their own set of issues such as lack of privacy or require specific types of technology. Access to information and support systems like the library or academic centers also becomes more challenging for students to navigate and life beyond the classroom can interfere in unequal ways for students (e.g. needing to spend more time caring for family members or working).

Wellbeing and Stress

Grade anxiety has always been a challenge for college students, but right now, that stress is being compounded by the myriad of factors students are trying to cope with during this time of sustained crisis. Health fears, racial injustice, home dynamics, Zoom fatigue, learning in different modes, isolation, etc. all contribute to students’ stress and ability to perform and engage in your course. It’s important to remember that stress is not distributed equally and while many of these factors are outside of your purview as the instructor, these factors do contribute to your students’ wellbeing, and student well-being is an important contributor to academic performance.

When designing assessments for your course, try to avoid adding any unnecessary stress to students’ learning experiences. In addition, acknowledge that students are coming from different circumstances and that there are certain limitations to remote learning (e.g. technology and time zones) that prevent you from replicating the same assessment you had in face-to-face courses

Purpose of the Assessment

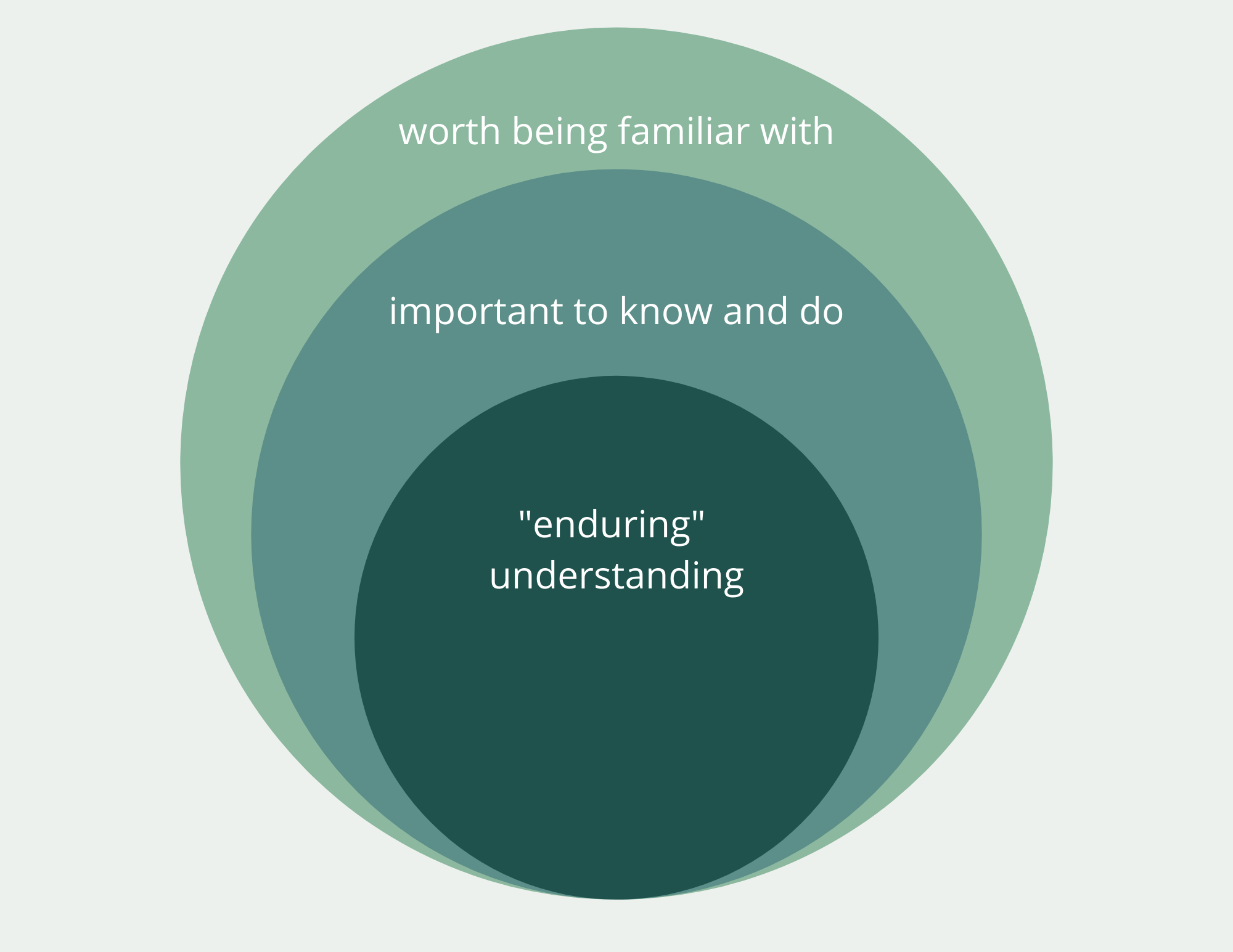

Once you have set your learning objectives using backward design, begin redesigning your assessments as evidence for student learning. Ask yourself, What do you want your students to learn? You can use Wiggins and McTighe’s three tier set of questions to help you form your curricular priorities.

- What do you prioritize as enduring understanding?

- What is important to know and do?

- What is worth being familiar with?

Once you have organized those priorities, design assessments that produce evidence of that learning.

Transparency

Be transparent with students about assessment purposes, procedures and criteria. Winkelmes (2013) developed the TILT (Transparency in Teaching and Learning) framework as a helpful way for instructors to design effective assessments that support student learning.

Purpose: Be explicit about the purpose of your course objectives with students.

Task: Explain and show your students what you intend for them to do. Consider scaffolding assignments into discrete manageable units that require constant low stakes assessment and show examples of what you are looking for.

Criteria: Share the criteria you will use for assessment at the beginning of the assignment.

As you adapt your course for remote or hybrid learning ensure that your assessments are designed and shared with students in a transparent manner.

Academic Integrity

Maintaining academic integrity may be more challenging to monitor when remote. Here are a few quick tips for thinking about reinforcing academic integrity in your courses:

Review the Honor Code with students in class. Place it within an ethics lesson applicable to your course or in a discussion thread related to your discipline.

Develop assignments in which they have to make their thinking visible and show their work, emphasizing process.

Ask “un-google-able” questions in which they have to make connections between recent material and materials from a previous week’s or have them demonstrate their knowledge within a specific case study.

Accessibility and Autonomy

Creating assessments that are accessible to all students is important. For more information on accessibility see CARDS website and the Accessibility section. Providing flexibility is not only important for students with accommodations but can also benefit all students and the class as a whole. Offering students some autonomy (e.g. choose which quiz score to drop or mode to turn in an assignment) can relieve student anxiety and also give students agency to connect their own interests to the course (e.g. a student interested in film could post a video for their discussion board contribution). Providing options for students within a clearly structured assignment or set of assignments will help enhance student engagement.

Metacognition and Self-Assessment

One of the benefits of the implementation of new formats and modalities is that student learning will necessarily change as well. This comes with challenges, but it also presents an opportunity to foreground how this change in the typical ways of learning can bring the process of learning itself into focus. Students will be able to think critically about how they process information and transfer those learning skill sets to life beyond college. Here are a few suggestions for reinforcing self-assessment opportunities in your courses:

Create assignments and assessments that ask students to think about their own thinking and learning processes.

Use exam and assignment reflections. For example, begin an exam with a question asking students how they studied and end the exam with a question about what was difficult and/or how students might study for it differently. For assignments, ask students to include an answer about the skills needed to complete the assignment and have them conclude the assignment with a reflection on the process.

Course Pace

Instead of a high-stakes final paper and cumulative final exam, consider breaking down these substantial assessments into shorter, more frequent tasks. This method of low stakes assessments will support student learning in a few ways. First, this process creates dialogue and opens the conversation between professor and students early in the course, enabling an instructor to point students in the direction of more resources if needed. Second, it builds confidence because it gives students a realistic understanding of where they are at early in the semester, enabling them to be more attuned to progression through the material and opportunities to evaluate their own learning. Third, it increases motivation by deterring procrastination and keeping students engaged through constant accountability checks.

See the figures below as examples of low stakes assessments that do not put the burden on the instructor to constantly grade while also ensuring that students are given more and frequent opportunities for different forms of feedback. Figure 2 demonstrates how a high stakes assignment can be broken down into small low stakes assessments throughout the course to enhance the student learning process with more feedback, structure, and support.

Figure 1. Graph of types of assignments and assessments

| Quizzes | Automated via Canvas |

| Journal (problems, writing, reflection) | Grade a few entries / self-assessment |

| Questions, exit tickets | Completion |

| Discussion board posts | Completion or grade a few entries |

|

Practice exercises

|

Peer review |

| Annotations | Peer review |

| Anonymous polls | Via Zoom / PollEverywhere |

| Group collaborative writing or problem solving | Completion or assess whole group work at once |

Figure 2. Graph of low stakes assessment per assignment

| Assignment | Submitted | Assessed |

|---|---|---|

|

Proposal |

Submitted |

Peer review |

|

Abstract Thesis statement |

Presented in class |

Instructor review |

|

Outline |

Turned in via Canvas assignments |

Instructor meeting or voice memos |

|

Annotated bibliography |

Created collectively as a class |

Class discussion |

|

Literature Review |

Turned in Canvas assignments |

Instructor review |

|

Early-stage drafts of a paper |

Breakout rooms or anonymously passed to students via instructor | Peer review |

Effective Feedback

Feedback is an important pedagogical tool that offers students an opportunity to reflect on their progression in a course and identify ways to grow. Useful feedback is specific, timely, and aligns students with the goals of the course. Effective feedback, when paired with grades, helps students better understand course objectives and offers actionable steps for how they can progress towards meeting those objectives. In terms of student engagement, research indicates that students who frequently solicit, receive, and incorporate feedback are highly motivated to achieve academic success. Hattie and Timperley (2007) indicate that effective feedback should answer three major questions:

- Where am I headed? (What are the goals?)

- How am I going? (What progress is being made toward the goal?)

- Where to next? (What activities need to be undertaken to make better progress?)

Strategies for Providing Effective Feedback

- State your expectations and/or evaluation criteria beforehand. You might choose to communicate these expectations by developing a rubric for each assignment.

- Grade student work according to the assignment goals and set standards.

- Giving students feedback earlier rather than later in the term allows them to identify areas of improvement and make use of feedback as the course progresses. Receiving feedback early on can also be motivating for students and help them understand the learning objectives of the course.

- Implementing low-stakes assessments can be useful for gauging student understanding and providing opportunities for feedback before a substantial assignment.

- When providing feedback, prioritize from first to lower order concerns, as you may not be able to address all aspects of student work.

- Consider which aspects of the assignment are most important and weigh your time and feedback accordingly. For example, when grading an essay, you might choose to spend more time on the argument or analysis in the paper and less on grammar or typos.

- In your feedback, provide concrete specifics that help students understand what they should change or improve for future work. Consider how students will be able to apply your feedback as they progress in the course.

- Refresh your memory if you are responding to student work over several days. Review your comments from previous grading each time you start.

- Set a rough time limit for reading and responding to student work and stick to it. Don’t attempt to grade multiple assignments in one sitting without scheduled breaks. Take a break if you start to feel cranky, tired, or restless.

- Highlight strengths in addition to addressing weaknesses in student work

- Evaluate the work instead of the student as a person. Help students separate a critique of their work from a critique of their person.

- Avoid connecting praise with criticism: “good idea, but…”

Tips for Creating a Rubric

Rubrics can be a useful way to communicate expectations and standards to students. Rubrics can also help you provide detailed and constructive feedback for student work. The following are some strategies for constructing an effective grading rubric, which you may tailor depending on your specific needs.

Starting points for constructing a rubric

- What do you want to assess? Why? What do you hope to learn about student learning?

- What criteria or traits must be present in the student’s work to ensure that it meets course learning objectives?

- For each criterion or trait, what is a clear description of performance or achievement at each level?

- What numerical rating scheme will I use in the rubric? How will you convert each level of the rubric to a letter grade? Are there certain criteria that will be prioritized or weighed more heavily?

Structuring and using your rubric

- Useful areas of evaluation for your rubric include categories like Clarity, Organization, Analysis, Argument, Eye Contact, Data Analysis, etc.

- Include levels of performance as columns in your rubric. These can be labeled in progressive order from Excellent, Good, Borderline, Needs Work, and so on. Try to use only as many levels as you need, and be mindful of how you phrase these levels of performance. For example, you may consider avoiding "Poor" or "Failing."

- Include descriptions in the appropriate cells of the rubric, starting the highest & lowest levels of performance and filling in the middle columns last. Be sure to distinguish clearly between them.

- Be transparent with your students about how the rubric fits in to your grading philosophy, as well as the relative weight of each criterion.

Restructuring Online Lectures is adapted from Harvard Bok's Center for Teaching and Learning; Indiana University’s Center for Teaching and Learning; Harrington, 2020. Assessment materials adapted from Eisenberg et al., 2009; El Ansari et al., 2010; Wiggins and McTighe 1998; Scott, 2013. Strategies for Providing Effective Feedback adapted from Elon University's Time Saving Strategies for Feedback, 2015 and Wiggins 2012.